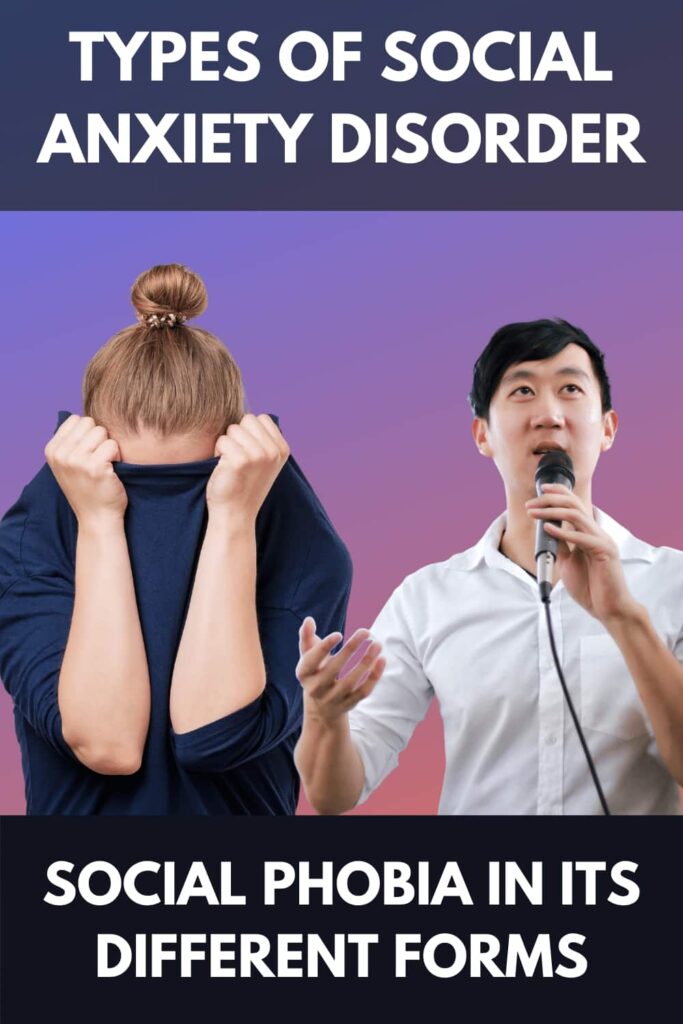

Types of Social Anxiety

Social anxiety, also called social phobia, refers to excessive concerns about being judged, rejected or negatively evaluated in social situations (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Every healthy person experiences some degree of social fears, but for most people these concerns are minor and do not cause any significant suffering.

However, for about 12% of the general population, their fears become so intense that they qualify for a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder (SAD) at some point in their lives (Kessler, Stein, & Berglund, 1998).

While all of these people may receive the same diagnosis, they often differ significantly from each other regarding their main symptoms and problem areas.

Here, we will have a look on these distinct manifestations of social fears, examining the different types of social anxiety.

Are There Different Types of Social Anxiety Disorder?

Not all people with social anxiety are alike.

Some may fear only a few specific scenarios, such as public speaking or dating, while others experience anxiety symptoms in virtually all social situations.

Likewise, some people are especially concerned about their behavior and appearing socially inept (e.g., “Saying this thing was so foolish“), whereas others may be particularly afraid of displaying observable anxiety symptoms, such as sweating, blushing, trembling, or a shaky voice.

In addition, social anxiety is often associated with introversion and shyness. While many people with SAD are shy and introverted, there are also many extroverted and outgoing people with social phobia.

Because these different types of social anxiety may benefit from different treatment approaches, experts have suggested several ways to divide SAD patients into different subgroups.

Let’s have a look on these proposals, before covering some very specific fears experienced by socially anxious people.

Classifying Social Anxiety Into Categories

In science, experts do not always agree. This also applies to the classification of socially anxious people into different subgroups.

There are multiple suggestions from different research teams. Below we will look at 3 different ways that can be used to classify people with social anxiety into different types.

- Classification according to the number of feared social situations.

- Classification according to the types of feared social situations.

- Classification according to the focus of the social fears.

Category I: Number of Feared Social Situations

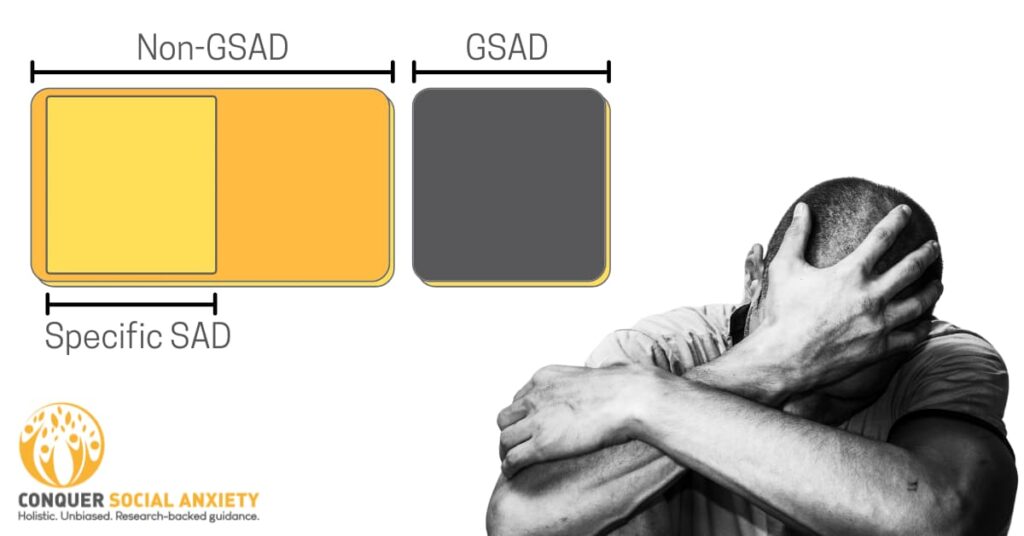

The idea behind this category is to distinguish between the number of social situations a person fears. This way you get 3 different types of social anxiety:

- Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder: Fear in virtually all social situations.

- Non-Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder: Fear in a limited number of social situations with at least one area of normal social functioning.

- Specific / Circumscribed Social Anxiety Disorder: Fear in only one or very few specific social situations.

Let’s have a quick look on each of them.

Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder

People affected by generalized social anxiety experience fear in virtually all or most social situations (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

This type of social anxiety usually starts in early childhood, typically before the age of 10 (Mannuzza et al., 1995).

People with generalized SAD tend to have a shy and anxious temperament, especially when confronted with new situations, experiences, and people.

This type of temperament is also referred to as behavioral inhibition (Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1987).

Compared to non-generalized SAD, people with GSAD have a higher chance of suffering from additional mental health conditions, such as depression or generalized anxiety disorder (Kessler, Stein, & Berglund, 1998).

In addition, people affected by this social anxiety type typically display greater difficulties living a “normal” life and often report having family members with a similarly inhibited temperament (Stein et al., 1998).

Therefore, the genetic component of generalized SAD seems to be more prominent than for non-generalized SAD.

Non-generalized Social Anxiety Disorder

The term non-generalized social anxiety is used to refer to any type of SAD in which the affected person retains at least one domain of normal social functioning (Heimberg, Holt, Schneier, Spitzer, & Liebowitz 1993).

This means that the range of people who fall into this category is very wide. Some suffer from anxiety in almost all social settings, while others experience it only in very few and specific situations.

In general, people with non-generalized SAD have less functional impairment than people with generalized SAD.

That is, many people with non-generalized social anxiety are able to maintain employment, pursue romantic relationships, have close friends, and so on.

This is usually not the case with generalized SAD, which tends to hit sufferers even harder as their social anxiety creeps into all areas of their lives.

If you’re interested in the negative effects that social anxiety often has on sufferers, click here to go to our article that discusses the ten most serious consequences of SAD.

Circumscribed (Specific) Social Anxiety Disorder

Circumscribed social anxiety (also: specific social anxiety) is experienced by people who fear only one or very few specific social situations.

Among people with SAD, public speaking anxiety is extremely common. Individuals who are only concerned about such scenarios would be classified in this type of SAD.

Compared to generalized SAD, the genetic component associated with circumscribed social anxiety is not as eminent. It also tends to start a little later, usually throughout puberty (Mannuzza et al., 1995).

It is also more likely that people with this type of social anxiety report traumatic social experience that marked the start of their social phobia (Öst, 1985).

For example, many people report being laughed at in class or a specific memory of being bullied.

People with circumscribed SAD may feel confident in most social situations and their friends and acquaintances would often not expect them to struggle with significant social fears.

Category II: Types of Feared Social Situations

Another suggestion on how to distinguish SAD sufferers is based on the type of situations they fear (Spokas & Cardaciotto, 2014). Here, the quantity of feared social scenarios is not a determining factor.

This category differentiates between the following three types of social anxiety:

- Anxiety in performance situations

- Anxiety in interaction situations

- Anxiety in observation situations

Social Anxiety in Performance Situations

Performance fears are very common in people with social anxiety disorder (Eng et al., 2000).

Some people seem to suffer only from fear of performance, as is the case for most people with public speaking anxiety.

For this group of people, being observed while not performing in front of an audience is no problem at all (Spokas & Cardaciotto, 2014). This also holds true for situations that require them to interact with others.

Compared to the other two types in this category, individuals with pure performance anxiety are less impaired, suffer less from additional mental disorders, and are less socially avoidant (Knappe et al., 2011).

However, when faced with a speaking task, this subgroup of people with SAD tends to experience more anxiety and react more strongly physiologically, such as experiencing increased heart rate, shortness of breath, increased sweating, etc. (Tran & Chambless, 1995; Boone et al., 1999).

Similar to the circumscribed SAD mentioned above, individuals with performance fear alone frequently report having experienced a traumatic performance situation that triggered their SAD (Stemberger, Turner, Beidel, & Calhoun, 1995).

Furthermore, other research teams found similarities in the physiological reactions of people with performance-limited SAD and panic disorder, and identified that, in many cases, a panic attack preceded the onset of their performance fears (Hofmann, Ehlers, & Roth, 1995; Nardi et al., 2009).

It should be noted that performance fears are very common among people with social anxiety.

The “performance only” type of social anxiety is characterized by the experience of performance fears only and a general absence of social fears related to other situations (Eng et al., 2000).

Social Anxiety in Interaction & Observation Situations

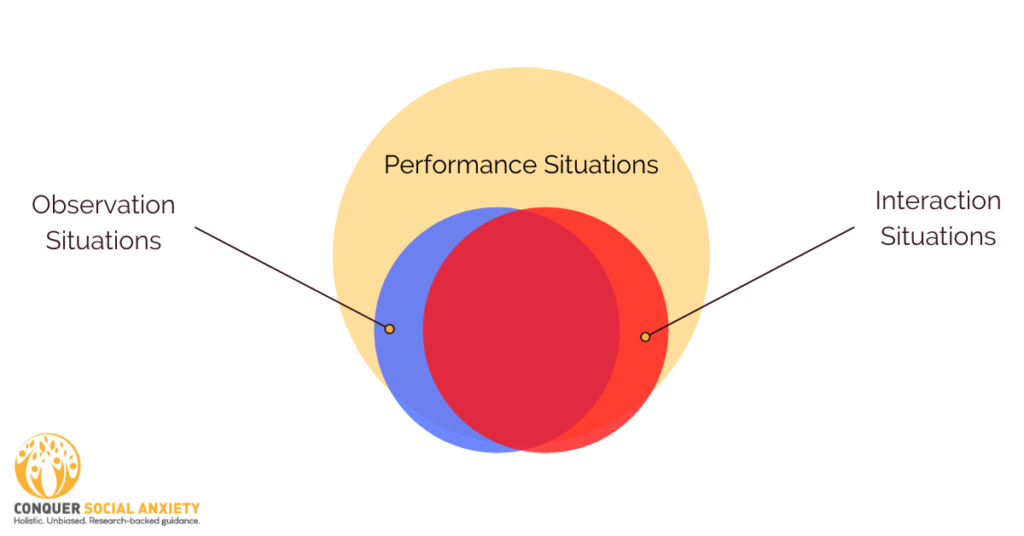

Although some experts have proposed differentiating between fear of interaction and fear of observation situations, there appears to be significant overlap between the two types (Cox, Clara, Sareen, & Stein, 2008; Ruscio et al., 2008).

That is, an overwhelming majority of people who experience fear of interaction situations, such as conversing with co-workers or a person they are attracted to, also fear observation situations, such as being observed while eating, drinking, or writing.

This relationship is bidirectional, which means that there are hardly any people suffering from SAD who fall into only one of the two categories.

What is more, most of the people who fear interaction and observation situations also fear performance situations. Have a look on the following graphic to understand how they tend to occur and relate to each other.

Researchers and experts are still unsure whether observation and interaction situations should be grouped separately or together, and whether or not these specifiers are useful at all.

Let’s look at the last form of subgrouping, which examines the focus of social fears.

Category III: Focus of the Social Fears

Most people with social phobia are excessively preoccupied with behaving in a way that is conducive to negative evaluation and rejection.

However, there appear to be two major deviations from this apparent core feature of SAD (Spokas & Cardaciotto, 2014).

One refers to the subset of SAD sufferers whose predominant fear is showing observable physical signs of anxiety, while the other relates to those who are primarily concerned about the possibility of offending others.

This means that this category is comprised of the following three types:

- Social anxiety focus: inept behavior

- Social anxiety focus: observable anxiety symptoms

- Social anxiety focus: offending others

Let’s examine these three types of social anxiety foci.

Social Anxiety Focus: Behavior

Fear of acting in a way that may lead to negative evaluation, rejection, disapproval, or humiliation is often considered the cardinal feature of SAD (Spokas & Cardaciotto, 2014).

And indeed, most people with SAD describe their main concern as behaving ineptly.

Individuals may worry about saying something silly, making a mistake, or behaving in a socially awkward manner.

To them, what they do is considered the main cause for concern.

For this reason, they keep a close eye on their own behavior and may even plan entire conversations in advance to make sure they don’t say anything that could be considered silly or foolish.

Social Anxiety Focus: Observable Anxiety Symptoms

A considerable proportion of people with SAD report showing observable signs of anxiety as their primary fear (Bögels and Reith, 1999).

Depending on the individual, the main concern may be physical reactions such as sweating, blushing, or trembling.

For others, it may be shortness of breath or fear of their voice cracking.

Often, the fear that the physical reaction will appear triggers the onset of the symptom.

When it does, affected individuals tend to become even more anxious or may feel embarrassed, which can further intensify their physical reactions.

In this way, a vicious circle can emerge that can lead to high levels of anxiety and avoidance of situations in which symptoms may arise.

It has been suggested that increased self-focused attention exacerbates physiological responses such as blushing (Bögels, 2006).

Individuals who fear showing physical anxiety symptoms often report related traumatic experiences, such as being teased about presenting these symptoms (Mulkens and Bögels, 1999).

Others may have additional medical conditions that cause their physical symptoms (Bögels et al., 2010).

For example, rosacea (skin condition causing redness), hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating), or essential tremor (involuntary tremor, often in the hands), may lead affected people to fear displaying the physical manifestations of their conditions in certain social situations.

To find out how to best deal with the physical symptoms of social anxiety, click here to be taken to our article describing appropriate strategies.

Social Anxiety Focus: Offending Others [Also: Taijin Kyofusho]

While the social anxiety types described so far are primarily concerned with the impression one leaves on others, this subtype is mainly concerned with the possibility of offending others and the effort to prevent this from happening.

In Japanese and Korean culture, this type of social anxiety is widespread and is referred to as Taijin Kyofusho (対人恐怖症).

It describes a persistent and excessive fear of offending others in social situations (Vriends, Pfaltz, Novianti, & Hadiyono, 2013).

In this subtype of SAD, the social fear focuses on doing something that is embarrassing to others, rather than doing something that is embarrassing to oneself (Iwase et al., 2000).

It has been suggested that this phenomenon is related to collectivist cultures that emphasize social harmony and interdependence (Rector, Kocovski, & Ryder, 2006).

However, it has been shown that people in Western cultures that uphold the same values may also exhibit symptoms of this type (Dinnel, Kleinknecht, & Tanaka-Matsumi, 2002).

It was suggested that the fear of offending others could be attributed to SAD’s central fear of negative evaluation, as upsetting others increases the risk of being rejected and disapproved of (Magee, Rodebaugh, & Heimberg, 2006).

Great, now you have a pretty good understanding of the basic social anxiety types. Next up, we will cover some specific phobias that include fears and anxiety in a number of different social situations.

Specific Types of Phobias & Syndromes Relating to Social Anxiety

In some cases, a person’s social fears are restricted to a very specific social situation and are only experienced in these settings.

According to the first category described above, individuals who meet these criteria would qualify as having circumscribed (also called specific) social anxiety.

In this section, we will briefly discuss some of the more common specific phobias that fall under the umbrella of social anxiety disorder.

Glossophobia: Public Speaking Anxiety

The term glossophobia, also public speaking anxiety, is used to refer to an intense fear of speaking in front of other people.

Glossophobia is widespread and is considered a subtype of SAD (Pull, 2012). Most people with generalized SAD are affected by it.

However, even people without social phobia often struggle with this specific type of fear.

Affected individuals tend to experience physiological and psychological overreactions when speaking in front of an audience.

Erythrophobia: The Fear of Blushing

Facial blushing is a physiological reaction that usually accompanies feelings of embarrassment and functions as a social cue, signaling that we are aware that we have behaved in a socially unacceptable manner.

However, when the symptom exceeds the normal limits of socially accepted emotional expression, people can easily become afraid of this reaction (Laederach-Hofmann, Mussgay, Büchel, Widler, & Rüddel, 2002).

Erythrophobia is a common phenomenon in adolescents that tends to diminish with age. However, this is not always the case.

Very few people seek treatment for their fear of blushing, in part because there is a strong stigma attached to it and because their primary care physician may not take it seriously enough or be aware of the treatment options available.

Hyperhidrosis & the Fear of Sweating in Public

Hyperhidrosis – excessive sweating – is quite common in people with social anxiety, with about one in four people with SAD affected (Davidson, Foa, Connor, & Churchill, 2002).

In most of these cases, increased sweating is perceived as a potential reason for scrutiny, triggering feelings of social anxiety, causing considerable distress and often disability (Nahaloni & Iancu, 2014).

Experts are still unsure whether hyperhidrosis is the result of sweat gland dysfunction, increased emotional arousal in social situations or a combination of both.

Nevertheless, it has been shown that increased sweating seems to lower the threshold for the development of social anxiety (Nahaloni & Iancu, 2014).

Performance Anxiety & Stage Fright

Performance anxiety is a perfectly normal phenomenon, especially if the performance is being evaluated by a potentially judgmental audience (Bögels & Lamers, 2002).

Evaluation from others often results in important consequences for an individual, which can intensify feelings of anxiety (Bancroft, 2009).

For example, depending on an athlete’s performance at a critical point during a competition, they may be evaluated favorably or negatively.

This means that the athlete is running the risk of being negatively evaluated by their teammates, their coach, their fans, and even by themselves (Rowland & van Lankveld, 2019).

Possible consequences of such a negative evaluation may include disappointed teammates, less playing time in the next game, higher pressure to perform from fans, non-renewal of his or her contract with the team, and lower self-confidence, just to name a few.

The prospect of these possible consequences can understandably cause anxiety, and this anxiety can in turn have a negative impact on his or her performance.

People who suffer from severe stage fright have typically had this experience, which leads them to feel even more anxiety in performance situations that can be critical for them.

Sexual Performance Anxiety

Sexual performance anxiety is closely related to stage fright in that it is usually triggered by fear of the possible negative consequences of inadequate performance.

Especially in the early stages of a relationship, sexual activity is often associated with evaluation and its potential consequences.

Both parties may be concerned about their partner’s expectations and perceptions, and fear that not only will they feel embarrassed and ashamed if they do not perform “adequately,” but that their relationship itself may be damaged or put in jeopardy (Rowland & van Lankveld, 2019).

The prospect of such negative consequences can easily lead to anxiety, and anxiety is associated with sexual impairment (Dèttore, Pucciarelli, & Santarnecchi, 2013; van den Hout & Barlow, 2000).

This, of course, can create a vicious cycle in which negative consequences lead to even more concerns about “appropriate” sexual performance in future sexual encounters.

While the term dating anxiety is self-explanatory, heterosocial anxiety refers to fear in social situations that involve both sexes (Glickman & La Greca, 2004).

However, this term excludes people who are attracted to people of their own sex. Therefore, we would like to point out that here we are referring to anxiety that occurs when interacting with people of the sex to which one is attracted.

In both dating anxiety and heterosocial anxiety, the anxiety response may be triggered by a mismatch between the desire to make a positive impression and the fear of not being able to do so.

Especially in people who place a lot of emphasis on winning over a potential partner and who at the same time suffer from low self-confidence, this can lead to strong feelings of social anxiety when dating or in other heterosocial situations.

If you are affected by dating anxiety, you can click here to go to our article on dating with social anxiety, which includes 15 helpful tips for more enjoyable dates.

Paruresis: Shy Bladder Syndrome

Paruresis is the inability to urinate in situations that may involve being scrutinized by others (Prunas, 2013). It is often also referred to as shy bladder syndrome.

Affected individuals usually worry about appearing strange or insecure if they cannot “let go” in the presence of others.

Because the underlying anxiety can be traced to concerns about being judged or negatively evaluated, it is classified as a type of social anxiety disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Parcopresis: Shy Bowel Syndrome

Similar to shy bladder syndrome, parcopresis describes the inability and/or difficulty to have bowel movements in public restrooms or otherwise in the presence of others, driven by fear of negative and unwanted evaluation by others (Knowles & Skues, 2016).

Shy bowel syndrome is associated with significant psychological distress in affected individuals and tends to diminish overall quality of life (Kuoch, Austin, & Knowles, 2019).

Feelings of embarrassment and shame, as well as a strong stigma, often hinder treatment seeking.

Olfactory Reference Syndrome: Fear of Smelling Bad

People suffering from olfactory reference syndrome are convinced that they give off an unpleasant smell (Pryse-Phillips, 1971).

Typical symptoms include repeated washing, frequent changes of clothing, excessive use of deodorants and perfumes, and restrictions on travel and social life.

Additionally, people with this condition are often convinced to receive negative feedback from others regarding their odor, such as negative gestures or even remarks.

Olfactory reference syndrome often causes sufferers to go to great lengths to reduce their body odor and spend much of their time worrying about their smell when they are with others (Begum & McKenna, 2011).

Eye Contact Anxiety

As we have pointed out, SAD is characterized by an excessive fear of being judged, negatively evaluated, or rejected.

It is believed that direct eye contact can trigger this fear and that socially anxious people therefore try to avoid it as much as possible (Schneier, Rodebaugh, Blanco, Lewin, & Liebowitz, 2011).

From an evolutionary perspective, this could be an adaptive strategy, as it signals to others that one is not a threat and willingly adopts a submissive position.

From the perspective of a socially anxious person, avoiding eye contact with higher-ups in the social rank system ensures that they will not become upset and possibly attack and reject them (Gilbert, 2001).

By avoiding the gaze of others, they may lose status in the social hierarchy, but they do not run the risk of being completely rejected and excluded.

Scopophobia: The Fear of Being Stared At

Similarly to eye contact anxiety, the fear of being starred at can be explained by the underlying fear of being judged and rejected, the hallmark of social anxiety disorder.

If this fear is excessive, it is also referred to as scopophobia (Stanborough, 2020).

From an evolutionary perspective, being stared at can signal potential danger. If we are eyed critically by others or simply stared at for a longer period of time, the human brain perceives a social threat and sounds the alarm.

For this reason, some people become anxious at the mere thought of being stared at or of being critically observed.

Deipnophobia: Fear of Eating and/or Drinking in Public

A significant number of people experience feelings of anxiety and intense insecurity when eating or drinking in public.

Excessive fear of eating in public is also known as deipnophobia (Rittenhouse, 2021).

Some may fear going to a restaurant alone because they think others could think they are weird or they do not have friends, while others are afraid of having to talk to their companions or that others will notice their shaking hands.

If the fear results from concern about being negatively evaluated or judged, it is considered a form of social anxiety.

Bibliophobia: Fear of Reading in Public

Many people who fear reading out loud to others have had a traumatic social experience that caused the onset of their excessive fear.

If you’d like to learn more about the fear of reading aloud, click here to be taken to our article on this phenomenon, which discusses causes and remedies.

Scriptophobia: Fear of Writing in Public

Just as some people are afraid of eating in public, because others may notice their hands shaking, others can be afraid of writing in public.

However, if the person is afraid to put his or her name on a contract, the underlying fear is probably of a different nature. In this case, we would not speak of social phobia.

To be classified as a form of social anxiety, the underlying anxiety must be based on the fear of being negatively evaluated by others.

Please note that this list is by no means exhaustive. In general, if a person has excessive anxiety about one or more specific social scenarios and the main concern is about being negatively evaluated, judged, or rejected, it is most likely a specific type of social anxiety.

However, several criteria must be met in order to receive a diagnosis. If you want to learn more, click here to go to our article about the diagnostic criteria for SAD.

Also, do not miss out on our free 7-day email course.

It will help you gain insight into your triggers and symptoms, learn practical tools for both short-term and long-term anxiety relief, and get on the path to a happier, more confident you with expert guidance.

Pin | Share | Follow

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_SOCIAL_ICONS]American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053

Bancroft, J. H. J. (2008). Human sexuality and its problems. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Begum, M., & McKenna, P. J. (2011). Olfactory reference syndrome: a systematic review of the world literature. Psychological medicine, 41(3), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710001091

Bögels, Susan M. (2006). Task concentration training versus applied relaxation, in combination with cognitive therapy, for social phobia patients with fear of blushing, trembling, and sweating. Behaviour Research and Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.010

Bögels, Susan M., Alden, L., Beidel, D. C., Clark, L. A., Pine, D. S., Stein, M. B., & Voncken, M. (2010). Social anxiety disorder: Questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety.

Bögels, S. M., & Lamers, C. T. (2002). The causal role of self-awareness in blushing-anxious, socially-anxious and social phobics individuals. Behaviour research and therapy, 40(12), 1367–1384. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00096-1

Bögels, S. M., & Reith, W. (1999). Validity of two questionnaires to assess social fears: The Dutch social phobia and anxiety inventory and the blushing, trembling and sweating questionnaire. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022812227606

Bögels, Susan M., Rijsemus, W., & De Jong, P. J. (2002). Self-focused attention and social anxiety: The effects of experimentally heightened self-awareness on fear, blushing, cognitions, and social skills. Cognitive Therapy and Research. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016275700203

Bögels, Susan M., Sijbers, G. F. V. M., & Voncken, M. (2006). Mindfulness and task concentration training for social phobia: A pilot study. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1891/jcop.20.1.33

Boone, M. L., McNeil, D. W., Masia, C. L., Turk, C. L., Carter, L. E., Ries, B. J., & Lewin, M. R. (1999). Multimodal comparisons of social phobia subtypes and avoidant personality disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(99)00004-3

Cox, B. J., Clara, I. P., Sareen, J., & Stein, M. B. (2008). The structure of feared social situations among individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of social anxiety disorder in two independent nationally representative mental health surveys. Behaviour Research and Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.011

Davidson, J. R., Foa, E. B., Connor, K. M., & Churchill, L. E. (2002). Hyperhidrosis in social anxiety disorder. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 26(7-8), 1327–1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00297-x

Dèttore, D., Pucciarelli, M., & Santarnecchi, E. (2013). Anxiety and female sexual functioning: an empirical study. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 39(3), 216–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.606879

Dinnel, D. L., Kleinknecht, R. A., & Tanaka-Matsumi, J. (2002). A cross-cultural comparison of social phobia symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 24(2), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015316223631

Eng, W., Heimberg, R. G., Coles, M. E., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2000). An empirical approach to subtype identification in individuals with social phobia. Psychological Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799002895

Erwin, B. A., Heimberg, R. G., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2003). Anger experience and expression in social anxiety disorder: Pretreatment profile and predictors of attrition and response to cognitive-behavioral treatment. Behavior Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80004-7

Furmark, T., Tillfors, M., Stattin, H., Ekselius, L., & Fredrikson, M. (2000). Social phobia subtypes in the general population revealed by cluster analysis. Psychological Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799002615

Gilbert P. (2001). Evolution and social anxiety. The role of attraction, social competition, and social hierarchies. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 24(4), 723–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70260-4

Glickman, A. R., & La Greca, A. M. (2004). The Dating Anxiety Scale for Adolescents: Scale development and associations with adolescent functioning. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(3), 566–578. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_14

Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Schneier, F. R., Spitzer, R. L., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1993). The issue of subtypes in the diagnosis of social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1016/0887-6185(93)90006-7

Hofmann, S. G., Ehlers, A., & Roth, W. T. (1995). Conditioning theory: a model for the etiology of public speaking anxiety? Behaviour Research and Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00072-R

Hook, J. N., & Valentiner, D. P. (2002). Are specific and generalized social phobias qualitatively distinct? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice.

Iwase, M., Nakao, K., Takaishi, J., Yorifuji, K., Ikezawa, K., & Takeda, M. (2000). An empirical classification of social anxiety: Performance, interpersonal and offensive. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences.

Kagan, J., Reznick, J. S., & Snidman, N. (1987). No Title. Child Development, 58(null), 1459.

Kashdan, T. B., & Collins, R. L. (2010). Social anxiety and the experience of positive emotion and anger in everyday life: An ecological momentary assessment approach. Anxiety, Stress and Coping. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800802641950

Kashdan, T. B., & Hofmann, S. G. (2008). The high-novelty-seeking, impulsive subtype of generalized social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety.

Kashdan, T. B., McKnight, P. E., Richey, J. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2009). When social anxiety disorder co-exists with risk-prone, approach behavior: Investigating a neglected, meaningful subset of people in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. Behaviour Research and Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.03.010

Kessler, R. C., Stein, M. B., & Berglund, P. (1998). Social phobia subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey. The American journal of psychiatry, 155(5), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.5.613

Knappe, S., Beesdo-Baum, K., Fehm, L., Stein, M. B., Lieb, R., & Wittchen, H. U. (2011). Social fear and social phobia types among community youth: Differential clinical features and vulnerability factors. Journal of Psychiatric Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.002

Knowles, S. R., & Skues, J. (2016). Development and validation of the Shy Bladder and Bowel Scale (SBBS). Cognitive behaviour therapy, 45(4), 324–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1178800

Kuoch, K. L., Austin, D. W., & Knowles, S. R. (2019). Latest thinking on paruresis and parcopresis: A new distinct diagnostic entity?. Australian journal of general practice, 48(4), 212–215. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-09-18-4700

Laederach-Hofmann, K., Mussgay, L., Büchel, B., Widler, P., & Rüddel, H. (2002). Patients with erythrophobia (fear of blushing) show abnormal autonomic regulation in mental stress conditions. Psychosomatic medicine, 64(2), 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200203000-00022

Magee, L., Rodebaugh, T. L., & Heimberg, R. G. (2006). Negative evaluation is the feared consequence of making others uncomfortable: A response to Rector, Kocovski, and Ryder. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.929

Mannuzza, S., Schneier, F. R., Chapman, T. F., Liebowitz, M. R., Klein, D. F., & Fyer, A. J. (1995). Generalized Social Phobia: Reliability and Validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950150062011

Mulkens, S., & Bögels, S. M. (1999). Learning history in fear of blushing. Behaviour Research and Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00022-4

Nahaloni, E., & Iancu, I. (2014). Harefuah, 153(10), 595–624.

Nardi, A. E., Lopes, F. L., Freire, R. C., Veras, A. B., Nascimento, I., Valença, A. M., … Zin, W. A. (2009). Panic disorder and social anxiety disorder subtypes in a caffeine challenge test. Psychiatry Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.023

Öst, L.-G. (1985). Ways of acquiring phobias and outcome of behavioral treatments. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 23, 683-689.

Perugi, G., Nassini, S., Maremmani, I., Madaro, D., Toni, C., Simonini, E., & Akiskal, H. S. (2001). Putative clinical subtypes of social phobia: A factor-analytical study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

Prunas A. (2013). La sindrome della vescica timida [Shy bladder syndrome]. Rivista di psichiatria, 48(4), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1708/1319.14632

Pryse-Phillips W. (1971). An olfactory reference syndrome. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 47(4), 484–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1971.tb03705.x

Pull C. B. (2012). Current status of knowledge on public-speaking anxiety. Current opinion in psychiatry, 25(1), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834e06dc

Rector, N. A., Kocovski, N. L., & Ryder, A. G. (2006). Social anxiety and the fear of causing discomfort to others. Cognitive Therapy and Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9050-9

Rittenhouse, M. (2021, February 23). Deipnophobia: Food and eating anxiety in public. Eating Disorder Hope. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.eatingdisorderhope.com/blog/deipnophobia-food-and-eating-anxiety-in-public#:~:text=Experiencing%20anxiety%20over%20eating%20in,necessary%20evil%20to%20staying%20alive.

Rowland, D. L., & van Lankveld, J. (2019). Anxiety and Performance in Sex, Sport, and Stage: Identifying Common Ground. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1615. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01615

Ruscio, A. M., Brown, T. A., Chiu, W. T., Sareen, J., Stein, M. B., & Kessler, R. C. (2008). Social fears and social phobia in the USA: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001699

Schneier, F. R., Rodebaugh, T. L., Blanco, C., Lewin, H., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2011). Fear and avoidance of eye contact in social anxiety disorder. Comprehensive psychiatry, 52(1), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.04.006

Spokas, M. E., & Cardaciotto, L. (2014). Heterogeneity Within Social Anxiety Disorder. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Social Anxiety Disorder.

Stanborough, R. J. (2020, April 16). Scopophobia: The fear of being started at. Healthline. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.healthline.com/health/scopophobia#:~:text=Scopophobia%20is%20an%20excessive%20fear,though%20you’re%20being%20scrutinized.

Stein, M. B., Chartier, M. J., Hazen, A. L., Kozak, M. V., Tancer, M. E., Lander, SheilaçFurer, P., … Walker, J. R. (1998). A Direct-interview Family study of Generalized Social Phobia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.1.90

Stein, M. B., Torgrud, L. J., & Walker, J. R. (2000). Social phobia symptoms, subtypes, and severity: Findings from a community survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1046

Stemberger, R. T., Turner, S. M., Beidel, D. C., & Calhoun, K. S. (1995). Social Phobia: An Analysis of Possible Developmental Factors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.104.3.526

Tran, G. Q., & Chambless, D. L. (1995). Psychopathology of social phobia: Effects of subtype and of avoidant personality disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1016/0887-6185(95)00027-L

van den Hout, M., & Barlow, D. (2000). Attention, arousal and expectancies in anxiety and sexual disorders. Journal of affective disorders, 61(3), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00341-4

Voncken, M. J., & Bögels, S. M. (2009). Physiological blushing in social anxiety disorder patients with and without blushing complaints: Two subtypes? Biological Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.02.004

Vriends, N., Pfaltz, M. C., Novianti, P., & Hadiyono, J. (2013). Taijin kyofusho and social anxiety and their clinical relevance in indonesia and Switzerland. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00003

About the Author: Martin Stork

Martin is a professional psychologist with a background in physical therapy. He has organized and led various support groups for people with social anxiety in Washington, DC and Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is the founder of Conquer Social Anxiety Ltd, where he operates as a writer, therapist and director. You can click here to find out more about Martin.