Mindfulness Meditation for Social Anxiety

This article contains a recommendation for a meditation app that we recommend for people with social anxiety. If you use this link, you may benefit from a significant discount and we will receive a commission.

In recent years, mindfulness has become a buzzword. You hear and read about it virtually everywhere.

But why exactly is that? What does it even mean to be mindful? Are mindfulness and meditation the same thing? And how in the world can it help people with social anxiety disorder (SAD)?

In this article, we will cover all of these questions and provide a thorough, comprehensive introduction to mindfulness meditation.

Alongside scientific insights on the profound effects of mindfulness on the brain, we will present you to a couple of practical exercises to introduce you to the meditative process.

Without further ado, let’s deep dive into one of the major tools to handle and counteract feelings of social anxiety.

Meditation & Social Anxiety Disorder

Before exploring what mindfulness meditation exactly refers to, let’s have a look at why it is worthwhile to educate yourself about it if you suffer from social phobia.

Despite the existence of effective treatments for social anxiety disorder, research steadily advances to improve the results of therapeutic approaches.

Far too many people do not respond to traditional CBT treatment and the greatest part of SAD sufferers never even seek professional help (Coles, Turk, Jindra, & Heimberg, 2004; Grant et al., 2005).

In recent years, mindfulness meditation has received a lot of attention from researchers all around the world. It has been proven to be an effective intervention for various mental health disorders, such as depression.

This raises an important question: Can meditation cure social anxiety?

Mindfulness meditation represents a new, promising intervention for people with social anxiety disorder. The recent mindfulness wave in Western culture has led researchers to investigate the effects of incorporating meditation practices into social anxiety treatment, with promising results.

As you will see in this article, the effects of mindfulness on the brain are manifold and compelling, especially for people with social phobia.

In order to understand how these changes take place and why socially anxious people tend to benefit from them, let’s examine what ‘being mindful’ actually means.

Introduction to Mindfulness: An End In And Of Itself

Mindfulness has been described as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally”, by Jon-Kabat-Zinn (1994), who famously created the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program.

Its main principles date back to ancient Buddhist and Hindu traditions, and emphasize acceptance of the present experience, without the intention of altering it in any way.

Furthermore, mindfulness highlights to actively notice the present moment and cultivate an increased awareness of evolving psychological experiences (Herbet, Gershkovich, & Forman, 2014).

Here are the three main components of mindfulness summarized:

- actively take notice of the present moment,

- cultivate an increased awareness of ongoing psychological experiences,

- accept the present experience without trying to change it in any way.

If this sounds too abstract for you, bear with us for another moment. Once you try the process for yourself, these concepts will be easier to grasp.

Mindfulness & Meditation: What’s The Difference?

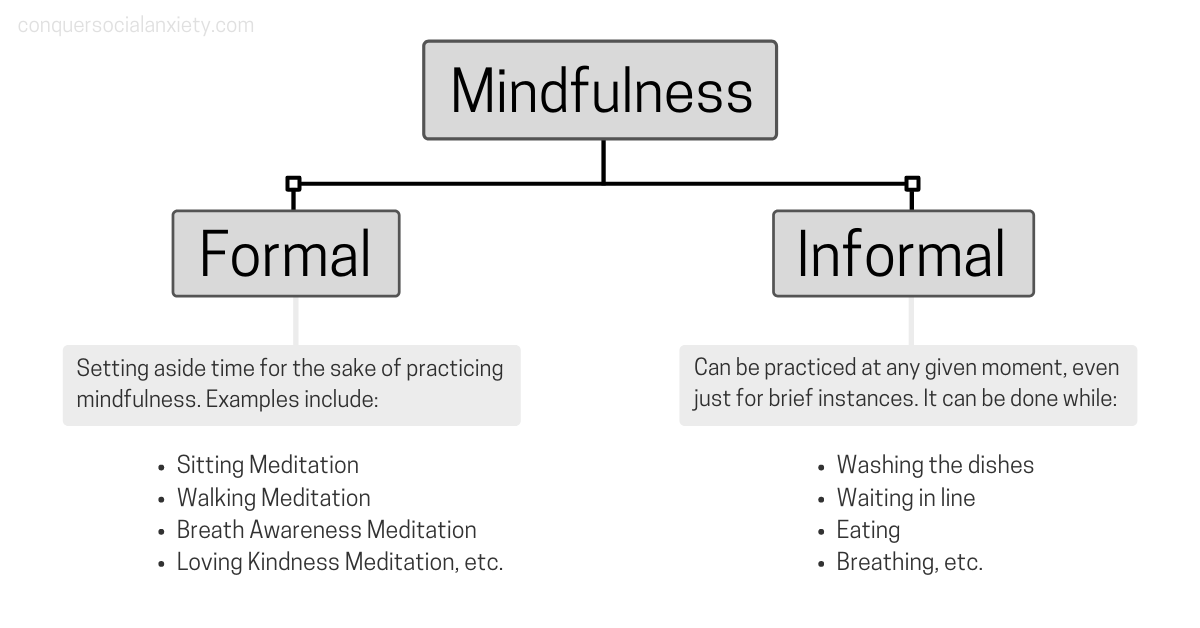

Mindfulness and meditation are often used interchangeably. However, strictly speaking, they are not the same thing.

Mindfulness and meditation are not synonyms. Meditation can be regarded as a method to practice mindfulness, while mindfulness is best viewed as a psychological state, which can be accessed through different techniques and practices, of which meditation is one (Marchand, 2012).

This means that you are mindful when practicing meditation. However, there are additional ways to practice mindfulness without engaging in formal meditation practice.

As you can see, meditation forms part of formal mindfulness practices. There are a wide range of different meditations.

However, before getting to know them in more detail, it is important to understand the basic principles of the meditative process.

Getting Started With Mindfulness Meditation

Let’s do a quick practical exercise to comprehend how meditation works. The best way to understand the principle of mindfulness is to experience it first hand.

Make sure you will not be disturbed for the next couple of minutes, find a quiet place and a comfortable position and hit play on the following video.

How did you do? Were you able to focus on the present moment? Or did you find yourself lost in thought every few seconds?

Getting lost in thought, realizing it and refocusing your attention is the main principle of mindfulness meditation.

This means that there is no right or wrong as long as you always come back to the present moment once you realize you have drifted off. No matter if you do so every two seconds.

When meditating, to fail is a desired part of the process. Dan Harris describes each drifting off and re-focusing as a “biceps curl for your brain”.

Put like that, the concept is not that difficult to grasp, right?

If you’re new to mindfulness meditation, or if you’ve tried it before and it never really clicked for you, using a meditation app can be a great way to get started. We have found Headspace to be by far the best option available.

For those dealing with social anxiety, it can be especially helpful as it provides users with tools to develop a more positive and compassionate attitude toward themselves and others, which can be beneficial in managing social anxiety symptoms.

It also makes it easy to really grasp and get used to the practiced, as it provides tons of guided meditations to help you get started.

To learn more about Headspace and its benefits, click the button below to explore what the app offers and download it for yourself. Depending on your plan, they will include a 7- or 14- day trial period for you to see if you like it.

By using this link, Headspace may share a small portion of their revenue with us, which helps us to dedicate our time to creating resources like this article. Using this link will not cost you anything extra. Thank you for supporting our work!

Are you a student? If so, you can get a significant discount using the link below. If you sign up through this link, Headspace will share a small portion of its revenue with us. Thank you for your support!

Now that you have a basic understanding of the meditative process, let’s see how mindfulness and meditation are used in psychotherapy.

Mindfulness in Psychotherapy: A Means to an End

Traditional mindfulness practices are viewed as an end in and of itself and are not used to enhance focus, well-being, or any other quality.

When it comes to psychological interventions, such as when incorporating mindfulness to cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), mindfulness is a means to an end, meaning that it is seen as a tool which can be used to improve treatment results (Herbert, Forman, & England, 2009).

Generally speaking, psychotherapy attempts to bring about improvements in well-being and help people live more fulfilled lives.

Oftentimes, this implies behavior change. It has been suggested that incorporating mindfulness in psychotherapy can help achieve these goals (Herbert, Gershkovich, & Forman, 2014).

Mindfulness-based psychotherapy interventions shift away from actively changing negative and irrational beliefs related to social situations (as is usually done in traditional CBT).

Instead, they accentuate acceptance of upsetting thoughts and feelings, while pursuing the change in behavior previously mentioned (Herbert, Gershkovich, & Forman, 2014).

Therefore, in contrast to traditional Hindu and Buddhist values, mindfulness in psychotherapy is not incorporated for the sake of doing it.

Instead, it is applied with the intention of reducing psychological suffering and bringing about improvements in well-being for the patient.

Research on the effectiveness of this strategy has been encouraging. Let’s have a look on some of the most important findings for those with social anxiety.

The Effects of Regular Mindfulness Practice on the Brain

Regular mindfulness practice leads to several adaptations in the brain. Let’s have a look at these changes by examining the most striking research findings of the last two decades.

Changes in Brain Structure

Your brain consists of ‘white matter’ and ‘gray matter’. Put very simply, gray matter is the site in which the information processing is done whilst the white matter contains the channels of communication.

Generally, increases in the mass or density of both types of tissue tends to correlate with increased mental performance. As we age, our white matter becomes less connective and our gray matter shrinks, resulting in cognitive decline.

However, studies have shown that both of these natural degradation processes have been significantly slowed in the brains of those who regularly practice mindfulness meditation.

Scientists have measured the white matter’s fractional anisotropy – the range of movement of water molecules – as a way of measuring its connectivity (Laneri et al., 2015). They found that, in most areas of the brain, meditators have a much weaker negative slope than non-meditators in the control group.

This suggests that meditation helps preserve the integrity of the white matter fibers that would typically deteriorate much quicker with age.

Equally, a group of people completely new to meditation who underwent an eight-week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction program (MSBR), showed increased gray matter in the left hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex, the temporo-parietal junction, and the cerebellum compared to the control groups that did not participate in MSBR (Hölzel et al., 2011).

Gray matter density has been shown to increase with regular mindfulness practice.

These areas of the brain are associated with concentration, learning and memory processes, emotion regulation, self-referential processing, and perspective taking. These structural changes suggest that long-term mindfulness practice could result in lower likelihood of developing brain-degeneration diseases such as Alzheimer’s (Lardone et al., 2018).

Further, mindfulness has been shown to consistently reduce the levels of cortisol and catecholamine in the brain – hormones which trigger anxiety and stress responses (Chen et al., 2012).

So, at both the neurobiological and neurochemical level, mindfulness has noticeable impacts on the organ of the brain itself. These physical changes are the counterparts of the psychological changes we will look at next.

Improvements in Cognitive Abilities

As you may be aware by now, mindfulness training often encompasses at least two types of practice: focused, one-pointed concentration – in which you attend to just one area of sensation, such as the breath at the nostrils – and open-awareness practice – in which you expand your attention to include a larger set of stimuli.

Studies suggest that the former aspect of mindfulness training could produce “significant improvements in selective and executive attention” – your ability to concentrate – whereas the latter could produce improved unfocused sustained attention abilities.

It has also been found that mindfulness training enhances working memory capacity – your ability to remember things on the go – and some executive functions like planning, impulse control and adaptive thinking (Chiesa, Calati, & Serretti, 2011).

These results suggest how mindfulness can play a role in helping improve many aspects of regular life.

The impact also extends to professional life: a 6-week online mindfulness training program created greater work engagement amongst employees of a company (Bartlett, Buscot, Bindoff, Chambers, & Hassed, 2021).

Similar results have been found on executive function skills in school children too, resulting in increased academic performance (Meiklejohn et al., 2012).

Mindfulness meditation has also been shown to improve spatial cognition. Participants who practiced mindfulness before doing the ‘mental rotation task’ (a test of how well you can predict how an object will look once rotated) performed better than those who didn’t (Geng, Zhang, & Zhang, 2011).

Improvements in Mental Well-Being

There is a lot of clear evidence that supports the idea that mindfulness practice has significant positive effects on many aspects of mental health.

These include improved subjective well-being, lessened symptoms of emotional reactivity, and improved behavior regulation (Keng, Smoski, & Robins, 2013).

Mindfulness also seems to reduce stress, ruminative thinking, emotional suppression and worry (Young, 2011). This leads to lower levels of both depression and anxiety amongst meditators (Parmentier et al., 2019).

This also extends to people who experience increased suffering and hardship in their lives. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in particular has been shown to reduce depression, anxiety and psychological distress in people with ongoing somatic diseases and general mindfulness training seemed to increase positive emotional affect amongst members of the military (Jha, Stanley, Kiyonaga, Wong, & Gelfand, 2010).

Further, for the soldiers, higher practice time was proportional with higher levels of positive emotional affect and decreased negative emotions. The more they practiced, the better the results.

The study also showed that the soldiers’ cognitive performance (namely, their working memory) also rose with increased mindfulness training, suggesting that mindfulness may help protect many aspects of psychological health in high-stress conditions.

Such results have been so compelling that the US military (and the armed forces of other nations) have begun adopting mindfulness training regimes for their members.

Mindfulness Meditation for Social Anxiety: Research Findings

Throughout the last two decades, researchers have been investigating the effects of mindfulness-based interventions for people with depression and anxiety disorders, including SAD.

One of the most researched programs is Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1990). MBSR is an eight week intervention which teaches participants mindfulness meditation practices.

Here are some of the most interesting research findings regarding MBSR for people with social anxiety:

- MBSR reduces anxiety in a wide range of disorders, including in people who do not qualify for an official diagnosis (Baer, 2003; Vøllestad, Nielsen, & Nielsen, 2012).

- It has been associated with reduced emotional reactivity (Ramel, Goldin, Carmona, & McQuaid, 2004).

- MBSR has been linked to enhanced emotional self-regulation (Goldin, & Gross, 2010; Lykins & Baer, 2009).

- It has been associated with improved attention regulation as well as interruptions of negative self-views (Goldin, Ramel, & Gross, 2009).

- MBSR has been linked to clinically significant reductions in anxiety along with improvements in mood and quality of life (Koszycki, Benger, Shlik, & Bradwejn, 2007).

- And, most importantly, it has been associated with improvements on social anxiety measures and well-being (Jazaieri, Goldin, Werner, Ziv, & Gross, 2012).

In addition to MBSR, there are slightly different approaches which are based on similar principles.

For instance, metacognitive therapy addresses socially anxious people’s beliefs about thinking (Wells, 2009).

Instead of directly targeting the content of upsetting thoughts in social situations, beliefs about the usefulness of attempting to control negative thoughts are questioned and acceptance of disturbing cognitions is advocated.

Another such approach is mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002). It also addresses social anxiety disorder from a metacognitive perspective, trying to promote a detached perspective regarding one’s personal experiences.

By adopting a more neutral, objective point of view, subjective suffering may decrease as a result. This is mainly achieved through mindfulness meditation practices, which are mostly derived from MBSR (Herbert, Gershkovich, & Forman, 2014).

So far, MBCT has shown promising results in the treatment of social anxiety (Bögels, Sijbers, & Voncken, 2006; Piet, Hougaard, Hecksher, & Rosenberg, 2010).

The common denominator of all these approaches is an increased awareness of what is happening on a psychological level at a given moment.

Through regular practice, you are likely to comprehend that you are neither your thoughts nor your emotions.

While these phenomena form part of your experience, you can learn to detach yourself from them.

Instead of getting carried away by your thoughts and emotions, you can decide to let them come up and be with you, without acting upon them.

Like this, you can break a lifelong habit of treating your thoughts as facts and as irresistible triggers for problematic emotions and behaviors.

In addition, through regular meditation practice you will strengthen your ability to direct your attention at will.

This skill comes in handy when you face stressful social situations, as people with SAD tend to focus on fear-provoking stimuli.

Through regular practice, you will be able to direct your attention to the task at hand, such as what you are saying or the conversation your are having. Like this, you will keep your social anxiety at bay and gain a sense of control an security.

If this does not make sense to you now, do not worry. This is totally normal. You will comprehend this as you start practicing mindfulness on a regular basis.

Speaking of which, let’s get you started with a couple of meditations specifically designed for people with social anxiety.

Guided Meditations for People With Social Anxiety

We hope that by now you are motivated to give mindfulness meditation a real shot.

Making formal meditation practice a daily habit can have a huge influence on your anxiety levels in social situations.

We created the following guided meditations for the specific needs of socially anxious people.

Feel free to try all of them and see which of them resonate most with you. Keep in mind that for substantial effects to take place, you need to practice regularly.

If you can, meditate every day for five to ten minutes. If you want to do more, that’s totally fine. Mindfulness is dose-dependent, meaning the more you meditate, the more you brain will respond to it.

In the beginning, you may want to practice with our guided meditations, as this will allow you to get a feel for the whole process.

Once you feel ready, you can meditate without external guidance. But more on that later.

Each of the following meditations fosters mindfulness and cultivates a particular aspect that is usually scarce in people with SAD.

Guided Self-Compassion Meditation

A common feature among socially anxious people is a marked tendency to judge themselves for their shortcomings (Cox, Fleet, & Stein, 2004).

This is especially true for their own social anxiety.

Most affected people think that being highly self-critical improves their chances of getting rid of their SAD. However, this could not be further from the truth.

By putting yourself down when you feel shy, anxious or embarrassed, you only add fuel to the fire and lower your sense of self-worth, when you actually need acceptance and support.

It has been found that self-compassion, the opposite of self-criticism, acts like a buffer against feelings of embarrassment and shame (Leary, Tate, Adams, Batts Allen, & Hancock, 2007).

Cultivating self-compassion should be among the top priorities for people with social phobia.

The following meditation has been designed to introduce you to the concept of self-compassion. Try it out and see how you feel.

Ideally, you repeat this meditation for a couple of days, so that the notion of treating yourself with kindness when you feel down really sinks in.

Whenever you notice that you criticize yourself harshly because of your SAD, come back to this meditation and remind yourself of the importance of being compassionate with yourself.

Compassion-based interventions are increasingly applied in social anxiety treatment and have led to promising results (e.g., Harwood & Kocovski, 2017).

To learn more about self-compassion, please head over to our article “How Self-Compassion Can Help With Social Anxiety“.

Next up, you will find a meditation that targets socially anxious people’s maladaptive habit of fighting their symptoms and suppressing their negative emotions.

Guided Acceptance Meditation for Social Anxiety Symptoms

Experiencing social anxiety symptoms can be highly uncomfortable. Therefore, it makes sense that people with social phobia try to suppress these distressing sensations.

However, more often than not do they fall prey to an insidious paradox: the more they try to fight and avoid their social anxiety, the more intense it becomes.

For this reason, instead of putting up a fight, the best strategy to handle symptoms of anxiety and embarrassment is to accept and tolerate them.

However, as this approach is counterintuitive, most affected people struggle with this.

The following meditation intends to foster a change of attitude, trying to plant the seed of acceptance. If you practice this meditation regularly, you will slowly grow accustomed to this new and different mindset.

As a result, you will stop fighting your negative thoughts, emotions and physical reactions. Instead, you will let them come up and be with you.

This way, you do not exacerbate your anxiety when it comes up and are more likely to keep it at bay.

Keep in mind that this process may take time to unfold. Positive effects of mindfulness exercises can usually be observed after several weeks of regular practice.

However, by reminding yourself to allow feelings of insecurity in stressful situations, you may experience less drastic spikes in your anxiety from day one.

Next up, we have a very well-known type of mindfulness practice waiting for you – loving kindness meditation. Of course, we have slightly adjusted it to fit the specific needs of socially anxious people.

Guided Loving Kindness Meditation

Loving kindness meditation represents one of the most applied mindfulness practices worldwide.

It aims to cultivate positive emotions and to direct them towards the self, others and all living beings.

Feelings of love, kindness and compassion activate the so-called affiliative system in our brains (Gilbert, 2014).

This system stands in marked contrast to the threat and competition systems, which tend to activate a consistent fight-flight-freeze response.

Socially anxious people mostly activate the last two systems, meaning that their body is usually under increased levels of stress and anxiety.

By activating the affiliative system, the threat and competition systems shut down. This gives our mind and body the chance to turn on a relaxation response and to release different types of hormones that promote well-being.

By engaging in regular loving kindness meditation, socially anxious people stimulate brain areas responsible for prosocial behavior.

Simultaneously, this practice can help them reconnect to their values, which often include close and loving relationships.

If this sounds too abstract or cocky to you, why not try it for yourself? Most people who give it a shot find loving kindness meditation very rewarding.

However, this type of meditation is not the right fit for everyone. Some people are repelled by the idea tof sending love towards themselves or to people they have ongoing problems with.

If you feel overwhelmed, feel free to stop at any time.

How did you feel? Were you able to generate feelings of kindness for yourself and others?

If this was hard for you, do not worry. This is totally normal. As you continue to practice, your brain will adjust and it will become easier to generate these emotions and positive intentions at will.

Informal Mindfulness Practice for Everyday Life

To see the fullest potential of how transformative mindfulness practice can be, it has to become part of everything you do. When you can be mindful every hour of the day, that’s when massive psychological shifts can happen.

However, you need not get anywhere close to this monastic level of practice to begin benefitting from it.

For many, just 10 minutes of formal practice a day can produce profound changes in your general well being and psychological state.

To progress from this point, many people decide to just increase their time spent in formal practice. Whilst this is great and certainly advisable, another way to progress is to begin to practice informally as well.

We define ‘formal mindfulness practice’ as time spent in stillness, typically sitting, with the intention of practicing a meditation technique for a pre-set, extended length of time. You also ideally focus on maintaining an upright posture.

In contrast, ‘informal mindfulness practice’ is any act of practicing a technique outside of your formal practice time. This may be done whilst walking somewhere, washing the dishes, doing the laundry, or during your commute to work.

Mindfulness is simply paying attention to your sensory experience in a systematic way and without judging or reacting, so it can be done at any time of the day in any place – in stillness or whilst in movement, in silence or surrounded by noise.

It also doesn’t have to be timed nor do you have to be in great posture.

Granted, it can be difficult to practice effectively whilst attending a sports match, or whilst taking a math exam, but it can be done. You can also practice whilst in conversation with people.

Again, this can be very difficult but will in fact be great practice, especially for those suffering with SAD.

When we learn to observe ourselves calmly and nonjudgmentally even during conversations that would typically be anxiety-provoking, we may find our social anxiety significantly diminished.

Informal practice can also constitute shorter bursts of sessions that resemble formal practice.

Whilst formal practice should be at least ten minutes per day, we can pepper in ‘micro-hits’ (a term coined by meditation teacher Shinzen Young) throughout the rest of our day.

A micro-hit is a short period of practice we can do at any point during the day where we are still and fully focused on the technique, as we would be during formal practice.

If we are finding a social interaction particularly challenging, we could always take a quick ‘toilet break’ and do a one or two minute micro-hit.

You may find it calming in the moment as well as conducive to maintaining mindfulness when you reenter the social situation.

Informal practice will become easier as your formal practice progresses.

At first you may only be able to stay somewhat present whilst, say, walking down a quiet street, but eventually, with practice, you could find yourself fully present and clear even in a loud, crowded stadium.

Starting with small challenges and picking the right techniques are key to staying on track.

If you are washing the dishes, for example, it may be instructive to focus on the external visual field, appreciating the flow of the soapy water.

Whilst listening to music, on the other hand, placing your attention on external sounds and inner feelings may be the most enjoyable and productive way to practice.

The same principles remain as with formal practice. Try to bring as much equanimity as you can to your experience. Notice its textures and movement.

When you notice you have become distracted, gently return your attention to the focus space you had originally chosen. If you are struggling, be soft and forgiving with yourself.

Also, do not miss out on our free 7-day email course.

It will help you gain insight into your triggers and symptoms, learn practical tools for both short-term and long-term anxiety relief, and get on the path to a happier, more confident you with expert guidance.

Pin | Share | Follow

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_SOCIAL_ICONS]

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

Bartlett, L., Buscot, M. J., Bindoff, A., Chambers, R., & Hassed, C. (2021). Mindfulness Is Associated With Lower Stress and Higher Work Engagement in a Large Sample of MOOC Participants. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 724126. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724126

Bögels, S. M., Sijbers, G. F. V. M., & Voncken, M. (2006). Mindfulness and task concentration training for social phobia: A pilot study. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1891/jcop.20.1.33

Chen, K. W., Berger, C. C., Manheimer, E., Forde, D., Magidson, J., Dachman, L., & Lejuez, C. W. (2012). Meditative therapies for reducing anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depression and anxiety, 29(7), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21964

Chiesa, A., Calati, R., & Serretti, A. (2011). Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clinical psychology review, 31(3), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003

Coles, M. E., Turk, C. L., Jindra, L., & Heimberg, R. G. (2004). The path from initial inquiry to initiation of treatment for social anxiety disorder in an anxiety disorders specialty clinic. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18(3), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00259-1

Cox, B. J., Fleet, C., & Stein, M. B. (2004). Self-criticism and social phobia in the US national comorbidity survey. Journal of Affective Disorders.

Geng, L., Zhang, L., & Zhang, D. (2011). Improving spatial abilities through mindfulness: effects on the mental rotation task. Consciousness and cognition, 20(3), 801–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2011.02.004

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Grant, B. F., Hasin, D. S., Blanco, C., Stinson, F. S., Chou, S. P., Goldstein, R. B., Dawson, D. A., Smith, S., Saha, T. D., & Huang, B. (2005). The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 66(11), 1351–1361. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v66n1102

Goldin, P., Ramel, W., & Gross, J. (2009). Mindfulness Meditation Training and Self-Referential Processing in Social Anxiety Disorder: Behavioral and Neural Effects. Journal of cognitive psychotherapy, 23(3), 242–257. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.23.3.242

Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion, 10(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018441

Harwood, E. M., & Kocovski, N. L. (2017). Self-Compassion Induction Reduces Anticipatory Anxiety Among Socially Anxious Students. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0721-2

Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., & England, E. L. (2009). Psychological acceptance. In W. O’Donohue & J. E. Fisher, (Eds.), General principles and empirically supported techniques of cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 77–101). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Herbert, J. D., Gershkovich, M., & Forman, E. M. (2014). Acceptance and mindfulness-based therapies for social anxiety disorder: Current findings and future directions. In J. W. Weeks (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of social anxiety disorder (pp. 588–607). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118653920.ch27

Hölzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Vangel, M., Congleton, C., Yerramsetti, S. M., Gard, T., & Lazar, S. W. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry research, 191(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006

Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R., Werner, K., Ziv, M., & Gross, J. J. (2012). A randomized trial of MBSR versus aerobic exercise for social anxiety disorder. Journal of clinical psychology, 68(7), 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21863

Jha, A. P., Stanley, E. A., Kiyonaga, A., Wong, L., & Gelfand, L. (2010). Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 10(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018438

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte Press

Keng, S. L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clinical psychology review, 31(6), 1041–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006

Koszycki, D., Benger, M., Shlik, J., & Bradwejn, J. (2007). Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behaviour research and therapy, 45(10), 2518–2526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.011

Laneri, D., Schuster, V., Dietsche, B., Jansen, A., Ott, U., & Sommer, J. (2016). Effects of Long-Term Mindfulness Meditation on Brain’s White Matter Microstructure and its Aging. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 7, 254. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2015.00254

Lardone, A., Liparoti, M., Sorrentino, P., Rucco, R., Jacini, F., Polverino, A., Minino, R., Pesoli, M., Baselice, F., Sorriso, A., Ferraioli, G., Sorrentino, G., & Mandolesi, L. (2018). Mindfulness Meditation Is Related to Long-Lasting Changes in Hippocampal Functional Topology during Resting State: A Magnetoencephalography Study. Neural plasticity, 2018, 5340717. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5340717

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887

Lykins, E. L. B., & Baer, R. A. (2009). Psychological functioning in a sample of long-term practitioners of mindfulness meditation. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(3), 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.23.3.226

Marchand W. R. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and Zen meditation for depression, anxiety, pain, and psychological distress. Journal of psychiatric practice, 18(4), 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000416014.53215.86

Meiklejohn, J., Phillips, C., Freedman, M. L., Griffin, M. L., Biegel, G., Roach, A., Frank, J., Burke, C., Pinger, L., Soloway, G., Isberg, R., Sibinga, E., Grossman, L., & Saltzman, A. (2012). Integrating mindfulness training into K-12 education: Fostering the resilience of teachers and students. Mindfulness, 3(4), 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0094-5

Parmentier, F., García-Toro, M., García-Campayo, J., Yañez, A. M., Andrés, P., & Gili, M. (2019). Mindfulness and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety in the General Population: The Mediating Roles of Worry, Rumination, Reappraisal and Suppression. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00506

Piet, J., Hougaard, E., Hecksher, M. S., & Rosenberg, N. K. (2010). A randomized pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and group cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adults with social phobia. Scandinavian journal of psychology, 51(5), 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00801.x

Ramel, W., Goldin, P.R., Carmona, P.E., & McQuaid, J.R. (2004) The Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Cognitive Processes and Affect in Patients with Past Depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research 28, 433–455 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000045557.15923.96

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. Guilford Press.

Vøllestad, J., Nielsen, M. B., & Nielsen, G. H. (2012). Mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The British journal of clinical psychology, 51(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02024.x

Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Guilford Press.

Young S. N. (2011). Biologic effects of mindfulness meditation: growing insights into neurobiologic aspects of the prevention of depression. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience : JPN, 36(2), 75–77. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.110010

About the Author: Martin Stork

Martin is a professional psychologist with a background in physical therapy. He has organized and led various support groups for people with social anxiety in Washington, DC and Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is the founder of Conquer Social Anxiety Ltd, where he operates as a writer, therapist and director. You can click here to find out more about Martin.