How to Help Someone With Social Anxiety? A Complete Guide

Feeling insecure in certain social situations is normal and adaptive.

When we perceive that we run the risk of conveying an undesirable impression on others, we may react with greater alertness, making sure that we do not behave in a way that may offend others or reflect poorly on ourselves (Leary, 2000).

However, for some people, feelings of insecurity around others are much more intense, resulting in outright anxiety that can be crippling and cause a whole host of problems for the individual concerned.

People who fall into this category either experience great distress when confronted with the social situations they fear, or they avoid these situations altogether (British Psychological Society, 2013).

Given the short-term benefits of the latter, it is often chosen over the former, a strategy that tends to have detrimental effects on people’s lives in the long term, leading to decreased functionality and life satisfaction.

Mental health professionals speak of social anxiety disorder (SAD; also called social phobia; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) to describe the presence of these symptoms.

Due to the nature of social phobia, affected individuals rarely ask for help. This makes it all the more important that their loved ones learn to support and accompany them in times of crisis and to look for long-term solutions.

This article is aimed at people who (suspect to) have a loved one with SAD.

We will provide you with everything you need to know about the condition in order to best support a person affected by social anxiety without stepping on their toes.

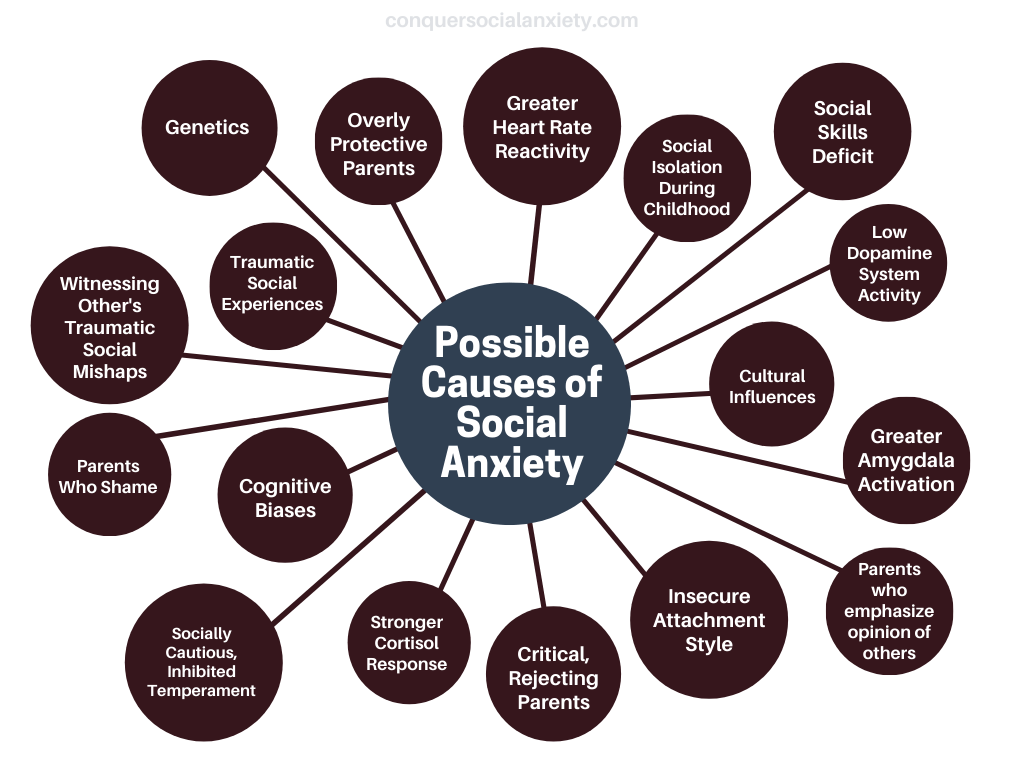

Although often assumed otherwise, social anxiety, like any other psychological phenomenon, has hardly any specific root cause.

Instead, it is usually the result of a unique mixture of several predisposing and contributing factors.

Genes often play a role, especially in those with a very shy and socially inhibited temperament.

However, there are a number of additional environmental, experiential and biological factors that can significantly influence the development of SAD.

The following list provides a quick overview of the current state of the science regarding the factors that can lead to the development of social phobia.

- Hereditary predisposing genetics (Spence & Rapee, 2016)

- An insecure attachment style (Bohlin, Hagekull, & Rydell, 2000; Muris, Mayer, & Meesters, 2000)

- Unfavorable parenting (e.g. Bögels, Van Oosten, Muris, & Smulders, 2001)

- Traumatic social experiences (Öst, 1985)

- Bearing witness to the social traumas of others (Öst & Hughdahl, 1981; Mineka & Cook, 1991)

- Challenging experiences as a child (Kessler, Davis, & Kendler, 1997; Magee, 1999; Lieb et al., 2000; Bandelow et al., 2004)

- Deficient social abilities (Spence, Donovan, & Brechman-Toussaint, 1999)

- Adverse means of directing attention (Alfano & Beidel, 2011)

- Predisposing biological features (e.g.,Condren, O’Neill, Ryan, Barrett, & Thakore, 2002).

- Cultural values and attitudes (e.g., Hofmann, Asnaani, & Hinton, 2011).

For a more detailed explanation of each of these factors, we recommend that you click here to access our article on the causes of social anxiety disorder.

Next, let’s look at how you may recognize that a person is affected by social anxiety.

As noted above, feeling insecure or a bit anxious in certain social situations is normal and often helpful.

For example, think about a first date or having to give a presentation to a large audience. You will probably agree that some concern for how you come across can help you make a better impression in these situations.

As most human beings experience these feelings of insecurity from time to time, they are not an indicator that a person has social phobia.

What distinguishes the concerns of people with SAD from those without it is that their worries are excessive (you can click here to go to our article on the diagnostic criteria for SAD).

This excessiveness is manifested either by frequent avoidance of the situations that trigger insecurity, or by intense anxiety reactions when confronted with them.

Depending on the individual, anxiety may manifest itself physically in the form of increased sweating, a trembling voice, shortness of breath, shaking hands, and so forth, or it may manifest itself in behavior that may be perceived as odd by others, such as extreme silence, being rude, or being overly talkative.

Other behaviors often observed in socially anxious individuals include increased submissiveness, excessive people-pleasing, and conflict avoidance.

However, there is also a small subgroup of people with SAD who present the opposite personality profile, marked by increased aggressiveness and risk-prone behavior (Kashdan, McKnight, Richey, & Hofmann, 2009). This group consists mainly of young men.

Although the above signs may be early indicators that a person may have social anxiety, there is no way of knowing for sure that an individual is affected by the condition without talking to him or her, as it is the subjective experience that really counts.

Depending on the person and your relationship with them, you may wonder whether you should address the issue openly or not.

The answer to this question is not generalizable, as each person will react differently to these attempts.

While some people may be eager to talk about their problem and welcome any attempt on your part to approach the subject, others might become very defensive and cut off any conversation that might reveal possible vulnerabilities or alleged character flaws.

Such a reaction is understandable, considering the high levels of embarrassment that affected individuals often experience in relation to their social anxiety and their own person in general.

That is, most people with SAD try to avoid being seen in a negative light, which usually leads them to be very critical of themselves and to hide their more “undesirable” parts from others.

Virtually all people with social phobia consider their SAD to be highly unattractive, so they are very ashamed of it and hope that no one will find out about it.

Therefore, having an open conversation on the subject can be very uncomfortable for those affected.

However, most affected people reach a point where they realize that their social phobia is not going to go away on its own and that they cannot solve their problem without help.

If you believe that your loved one has reached this point and that you have the kind of relational closeness to talk about intimate topics, he or she will most likely be receptive and appreciative when you bring up the subject.

However, make sure that this process is as easy and comfortable as possible for the affected person, so as not to frighten them and prevent them from opening up.

There is no magic formula on how to do this. You, as their loved one, are in the best position to choose the most promising path.

For very anxious people, who are prone to embarrass easily and have a strong tendency for panic attacks, you can initiate the conversation by text message.

This way, the person is not forced to confront face-to-face and can maintain some level of control over what they will share and whether or not they will open up in person down the road.

Here are a couple of guidelines to keep in mind when first addressing your loved one’s social anxiety:

- Be empathetic and understanding.

- Let them know that you are bringing up the subject because you care about their well-being, not to criticize them or point out their flaws.

- It may be helpful to share the social situations that make you feel insecure. Many people with SAD are surprised that social fears are quite common and normal. However, it is crucial that you communicate that you know their anxiety is much more intense and severe than yours or that of most people. You can also point out that about 10% of people have SAD at some point in their lives (Wittchen & Fehm, 2001).

- Communicate that you understand that it is not their fault or responsibility that they suffer from social anxiety.

- Let them know that you are here to support them. Some may find it helpful to have someone to practice certain social skills with, others to have someone to be there for them in difficult situations, or just someone to listen. The most important thing is for them to realize that they are not alone with their problem.

- Discuss the possibility of starting therapy and joining a local support group. There are several effective interventions for social anxiety (click here to access our e-book which provides a comprehensive summary of the most current state-of-the-art interventions for social phobia), but only 20% of sufferers receive professional help (Grant et al, 2005). You, as their loved one, can help them make the decision to give it a try.

As we have mentioned, socially anxious people are very concerned about the possibility that others will see them as weird, weak, stupid, useless, etc.

The last thing you want to do is reinforce their negative view of themselves. Make sure you treat them with respect, as an equal, as someone worthy of being taken seriously.

It is also important to keep in mind that, due to fear of being seen as inept, some people with SAD may minimize their struggle and pretend they are fine when they are really not.

This strategy can have detrimental consequences, as it can leave them suffering in silence with no realistic hope of improvement.

You, as their loved one who knows them well, are in the best position to be that helping hand they may so desperately need, even if they don’t explicitly ask for it.

Given their anxiety and their heightened sensitivity to criticism, which can often be difficult to understand for people who are not affected, there are a couple of nuances to consider when interacting with socially anxious people.

Depending on the person and their specific problem areas, different things may be critical so that they don’t feel too uncomfortable interacting with you.

The following is a list of behaviors and situations that tend to make people with social phobia feel uneasy:

- Drawing unwanted attention in group settings;

- having others point out their physical anxiety reactions;

- being described as unusually quiet;

- being pressured to talk about intimate topics;

- others being overtly informed of their social anxiety;

- being forced to confront their fears rather than choosing to do so themselves;

- being criticized and treated rudely;

- being excluded from group conversations and activities;

- being put on the spot in a group (“What do you think about this?“);

- being exposed to a situation that may reveal a lack of (social) competency.

These examples are fairly general and are shown here because they are the most important to you, someone who does not want to step on the toes of a person with social phobia.

Therefore, the above list is not an exhaustive depiction of the situations that people with SAD often struggle with. For a more detailed overview of the most feared situations, feel free to click here to go to our full introduction to social anxiety.

With the above information in mind, it is advisable that you tread carefully when interacting with your loved one and base your behavior with them on your knowledge of their personality and your intuition.

That is, your relationship with the socially anxious person is likely to benefit if you do not put them in the above situations and follow your instinct as to which situations, behaviors, and topics of conversation they may appreciate and which they may shy away from.

However, there is a fine line between being reasonably considerate of their difficulties and reinforcing their avoidance behavior, the latter being a maintaining factor of social anxiety (Clark & Wells, 1995).

At best, your relationship with the affected person is an ideal mix of consideration and understanding regarding their fears, as well as support and encouragement regarding their proactive improvement process.

Let’s see how you can achieve such a balance.

Without proper treatment, social anxiety disorder is marked by high persistence across the lifespan (Beesdo-Baum et al., 2012).

When SAD remains stable, affected people often develop depression and substance abuse (Sonntag, Wittchen, Höfler, Kessler, & Stein, 2000; Wittchen, 2000; you can click here to access our brief article on what happens when social phobia goes untreated).

For this reason, most socially anxious people benefit from taking a proactive attitude toward their psychological well-being, which usually involves breaking their pattern of social avoidance, one step at a time.

Because exposure to feared social scenarios can be very frightening and psychologically draining, many affected individuals will seek it out only sporadically, if they do so at all.

Having someone who encourages them, time and again, to voluntarily seek that exposure and reduce avoidance can be a game changer for many people.

However, it is important not to push too hard and to make sure they understand you encourage them for their own good.

To help your loved one understand the importance of repeated exposure to the feared situations, you may share our article on cognitive behavioral therapy for SAD with them, which you can access by clicking here.

It is important to keep in mind that there will be times when they will be motivated to face their fears, just as there will be times of low morale and increased social withdrawal.

Such fluctuations are quite normal in socially anxious people.

When you, as a caring and supportive person, notice these changes, you may want to adjust your behavior accordingly.

In general, you should avoid pushing too hard, just as you should avoid being too permissive with extreme withdrawal.

As the latter is a typical defense mechanism against their anxiety, it is important to respect their momentary agitation, but also to lend a hand to slowly bring them out of it.

Sudden drops in mood and motivation are to be expected, as they are a typical part of the improvement process.

However, these times are often critical, as affected individuals may miss work, school, college, university or important social events, which can have detrimental long-term consequences.

What matters most in these situations is that you support them during these times and find a gentle way to boost their morale and encourage them to become proactive again.

Here are a couple of recommendations that are often useful:

- Listen to what your loved one has to say if he or she is willing to talk. If they are not, let them know that you are always there to lend an ear, but don’t push them too hard.

- Remind them that feeling down and discouraged is a normal part of the process, which is to be expected. Those who get better usually understand this and, as a result, manage to pull through despite their low morale.

- If your loved one is having trouble with a particular social event coming up, offer to help him or her simulate and practice the dreaded situation.

- If they have missed a couple of days at their new job, college, etc., they may be inclined to think they have already lost face, which often leads to even more withdrawal and avoidance. Help them understand that returning to work, school, etc. is a valid option, and that others are unlikely to think as badly of them as they imagine.

- Psychological crises, such as an acute period of social withdrawal and avoidance, can serve as motivation to seek professional help. You may discuss the possibility of initiating a therapeutic process if you feel it is an appropriate time to do so.

Also, it is important to keep in mind that you can only do so much. Sometimes, people who are suffering are not receptive to others’ attempts to help them.

While it is your responsibility as a loved one to care about them and look for ways to support them, in the end it is the affected person themselves who has to take responsibility for their own well-being.

Do not get sick because you run against a wall when trying to help. If your loved one is not receptive, make sure they know you are willing to listen and help, but take care of yourself first.

As mentioned above, social anxiety disorder should normally be treated professionally, as it can persist or even increase over time if not treated adequately (Beesdo-Baum et al., 2012).

Although many people are still reluctant to seek help from psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors and/or psychotherapists, as depending on their country and region of residence the stigma may still be significant, this option is becoming increasingly well accepted.

If you think your loved one is struggling with fear of negative evaluation and anxiety in social situations, it is usually a good idea to have them consult with a mental health professional to see how serious their situation is and how they might be helped.

We want to emphasize that this help should be administered by professionals.

Online resources, such as this website, can be great tools to get a first idea and be guided in the right directions. However, potential diagnoses and corresponding treatments should only be carried out by mental health professionals who have been trained to do so.

If your loved one is willing to consult in person (face-to-face), they can talk to their primary care physician and ask for a referral to a psychologist, psychiatrist, counselor or psychotherapist.

Depending on their health insurance and country of residence, it may not be necessary to speak to their primary care physician and they may contact a mental health professional directly.

You can offer to accompany them to the treatment center, which can facilitate the process of seeking professional help.

If your loved one prefers to consult online, be aware that there are several valid options for doing so.

Online treatment is often especially appropriate for people with SAD, as it has the potential to lower the threshold for treatment seeking.

That is, not having to sit face-to-face with a stranger and open up about their insecurity increases the likelihood that socially anxious people will seek professional help.

If your loved one is inclined to try online therapy, we recommend BetterHelp. It’s an online portal that matches your loved one with a suitable therapist to help them with their social anxiety.

They offer online counseling and therapy services delivered through web-based interaction as well as telephone and text based communication.

If he or she chooses this option, we would appreciate it if they would click the above banner or use this link to sign up for online treatment with BetterHelp. This way, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to your loved one.

We rely on these contributions from our readers to create useful content such as this article. Thank you for your support!

In case the affected person is still a teenager, you may want to have a look at Teen Counseling, who specialize in matching children with qualified therapists for online treatment.

By using this link, you will be taken to their website. Here, too, we may gain a commission at no additional cost to you or your loved one if you decide to sign up. Thank you for supporting us this way!

Pin | Share | Follow

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_SOCIAL_ICONS]

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69–93). The Guilford Press.

Grant, B. F., Hasin, D. S., Blanco, C., Stinson, F. S., Chou, S. P., Goldstein, R. B., Dawson, D. A., Smith, S., Saha, T. D., & Huang, B. (2005). The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 66(11), 1351–1361. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v66n1102

Kashdan, T. B., McKnight, P. E., Richey, J. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2009). When social anxiety disorder co-exists with risk-prone, approach behavior: investigating a neglected, meaningful subset of people in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. Behaviour research and therapy, 47(7), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.03.010

Leary, M. R. (2000). Social anxiety as an early warning system: A refinement and extension of the self-presentational theory of social anxiety. In: S. G. Hofman, & P. M. DiBartolo (Eds.), Social phobia and social anxiety: An integration (pp. 321–334). New York: Allyn & Bacon.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Social Anxiety Disorder: Recognition, Assessment and Treatment. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society (UK); 2013. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 159.) 2, SOCIAL ANXIETY DISORDER. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK327674/

About the Author: Martin Stork

Martin is a professional psychologist with a background in physical therapy. He has organized and led various support groups for people with social anxiety in Washington, DC and Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is the founder of Conquer Social Anxiety Ltd, where he operates as a writer, therapist and director. You can click here to find out more about Martin.