Causes of Social Anxiety: A Thorough Exploration for Better Understanding

Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is a condition that affects millions worldwide, yet its causes remain as complex as the human mind itself.

While many people experience occasional nervousness in social situations, those with SAD endure a far more debilitating form of anxiety that can severely impact their quality of life.

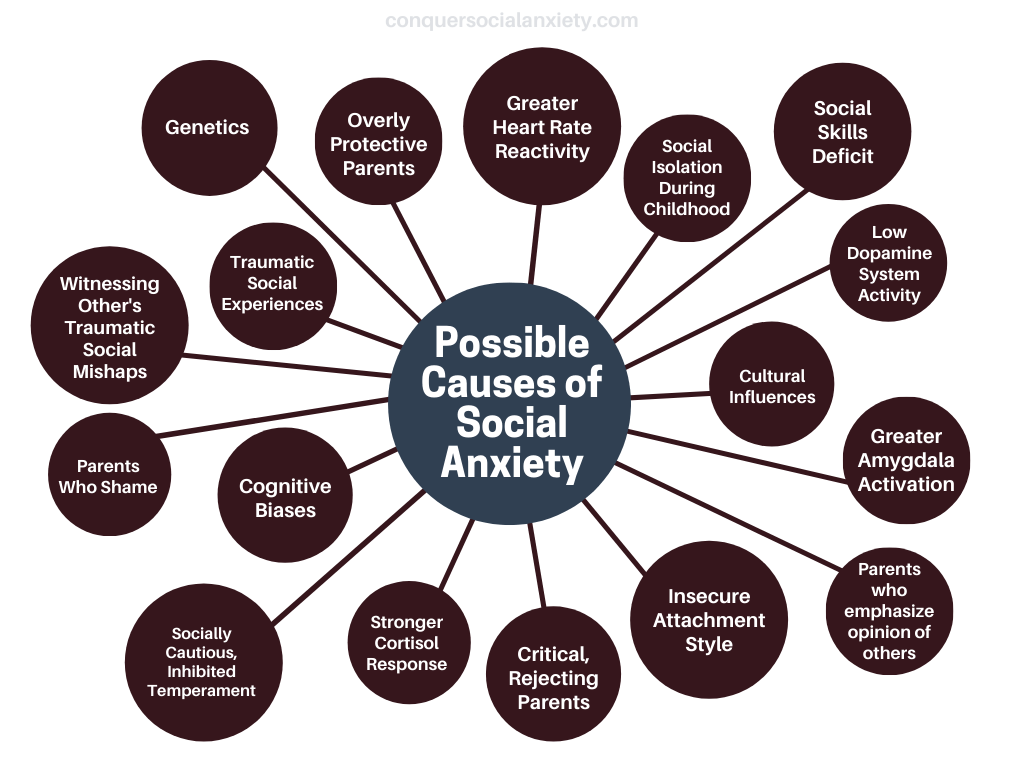

But what exactly leads to the onset of this disorder? Is it purely genetic, or do environmental factors play a role? Could societal norms and cultural influences also be contributing factors?

In this comprehensive guide, we delve into the multifaceted origins of social anxiety. From genetic predispositions and biological vulnerabilities to environmental influences and cultural nuances, we aim to provide a complete understanding of the factors that contribute to this condition.

Whether you’re a patient seeking answers or a healthcare provider looking to deepen your understanding, this article offers valuable insights into the complex world of Social Anxiety Disorder.

A. The Genetic Puzzle: More Than Just DNA

The Family Connection: Not Just a Coincidence

While science has yet to pinpoint a specific ‘social anxiety gene,’ the role of family history in the development of social anxiety disorder is hard to ignore.

The familial patterns observed among those with SAD offer compelling evidence that genetics may play a significant role in predisposing individuals to the disorder.

- Family History: Individuals with generalized social anxiety often report a family history of similar issues. It’s not uncommon to find multiple family members who either share the diagnosis or exhibit traits of social inhibition, such as extreme shyness or avoidance of social situations.

- Genetic Predisposition: The recurring patterns of social anxiety within families suggest a genetic predisposition. While the exact genes involved remain unidentified, research indicates that genetics can make some individuals more susceptible to developing SAD (Spence & Rapee, 2016).

- Nature vs. Nurture: It’s important to note that while genetics can predispose someone to SAD, it’s often the interaction between these genetic factors and environmental influences, such as upbringing and life experiences, that ultimately triggers the disorder.

- Ongoing Research: Scientists are actively studying the role of genetics in SAD, and advances in genetic research may soon provide more insights into the specific genes or gene clusters that contribute to the disorder.

Understanding the family connection in SAD not only helps us grasp the complexity of the disorder but also emphasizes the importance of early intervention, especially for those with a family history of social anxiety.

Beyond DNA: The Biological Underpinnings

While genetics lay the foundation, it’s essential to recognize that the biological factors contributing to social anxiety are multifaceted.

Emerging research has identified several intriguing biological markers that offer a more nuanced understanding of the disorder:

- Cortisol Response: Cortisol is often referred to as the ‘stress hormone,’ as it’s released during stressful situations. A study found that people with SAD exhibited a heightened cortisol response when performing in front of an audience, suggesting that their stress response mechanisms might be more reactive than those without the disorder (Condren et al., 2002).

- Dopamine System Activity: Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that plays a crucial role in regulating mood and social behavior. Preliminary research indicates that individuals with generalized SAD may have lower activity in their dopamine systems, which could affect their mood and social interactions (Schneier et al., 1994-1995).

- Serotonin Receptors: Serotonin is another neurotransmitter that plays a significant role in mood regulation. Some studies suggest that people with SAD may have hypersensitive serotonin receptors, making them more susceptible to mood swings and emotional imbalances (Aouizerate et al., 2004).

Understanding these biological markers can help us appreciate the complexity of SAD and pave the way for targeted treatments.

It’s worth noting that these markers are not definitive causes but rather contributing factors that interact with genetics, environment, and personal experiences to shape each individual’s experience with social anxiety.

B. The Emotional Foundations: Attachment and Parenting Styles

The Bond That Shapes Us: Attachment Theory Revisited

The concept of ‘attachment style‘, coined by psychologist John Bowlby in 1969, is a foundational element in understanding emotional well-being and social interactions.

Attachment styles are generally categorized into secure, anxious, and avoidant types.

A secure attachment style is formed when a child’s emotional needs are consistently met by their primary caregiver, which fosters a sense of security and self-worth that carries into adulthood.

However, when a caregiver is inconsistent in their emotional availability or responsiveness, an anxious or avoidant attachment style can develop.

Anxiously attached individuals may become overly dependent on others for validation, while avoidantly attached individuals may shun emotional closeness altogether. Both of these insecure attachment styles can serve as risk factors for developing social anxiety disorder.

Studies have shown that an insecure attachment style can predispose individuals to social anxiety, as they may constantly seek approval while fearing rejection or judgment (Bohlin et al., 2000; Muris et al., 2000).

This can manifest in various ways, such as an intense fear of public speaking, avoiding social gatherings, or even experiencing anxiety during everyday social interactions.

The Parental Blueprint: How Upbringing Influences Social Anxiety

Parenting styles can significantly impact the onset and severity of social anxiety.

For example, overprotective parents may limit their child’s exposure to social situations, preventing them from developing the necessary social skills and confidence.

Controlling parents may micromanage every aspect of their child’s life, leaving the child feeling incapable and anxious about making decisions on their own.

Emotionally distant parents may fail to provide the emotional support and validation that a child needs to feel secure and confident in social settings.

Research has linked these types of overcontrolling and rejecting parenting styles to the development of social anxiety disorder (Bögelset al., 2001; Wood et al., 2003).

Additionally, parents who place a high value on societal opinions may inadvertently pass on these anxieties to their children.

For instance, parents who frequently shame their children for not meeting societal expectations—like getting top grades or excelling in sports—can instill a fear of failure and a preoccupation with how they are perceived by others.

Such attitudes appear to be more common among parents of individuals with SAD (Bruch et al., 1989; Stravynski et al., 1989).

C. The Scars We Carry: Trauma and Social Skills

A Single Moment: The Impact of Traumatic Social Experiences

For many individuals with SAD, a single humiliating or distressing social event can serve as a catalyst for their anxiety.

Imagine a situation where someone is asked to read aloud in a classroom setting. They stumble over words, lose their place, and become aware of snickers and whispers from classmates.

This single event could be so emotionally scarring that even the thought of reading in public or speaking in a classroom setting triggers intense anxiety and fear.

This phenomenon, known as direct conditioning, activates fear responses in the brain, often triggered by merely thinking of a similar experience (Öst, 1985).

Learning Through Observation: The Ripple Effect

Interestingly, witnessing someone else’s traumatic social experience can also condition the brain to fear similar situations.

For example, imagine a student observing a classmate being harshly criticized and laughed at during a presentation.

Even though the observer wasn’t the one presenting, the emotional impact of witnessing this event could condition their brain to associate public speaking or classroom presentations with negative outcomes, thereby triggering anxiety in similar future situations.

This form of learning has been observed in non-human primates and suggests that individuals with socially anxious parents or siblings may be at higher risk for developing similar anxieties (Öst & Hughdahl, 1981; Mineka & Cook, 1991).

The Social Skills Paradox: Competence Versus Perception

People with SAD often underestimate their social abilities, despite evidence to the contrary.

For instance, they may believe they’re terrible at public speaking or can’t hold a conversation, even when they’ve successfully done so in the past.

This self-doubt can be so pervasive that it blinds them to their actual capabilities, leading to avoidance of social situations and further reinforcing their fears (Cartwright-Hatton et al., 2003; Cartwright-Hatton et al., 2005, Clark & Arkowitz, 1975; Norton & Hope, 2001; Rapee & Abbott, 2006; Rapee & Lim, 1992; Stopa & Clark, 1993; Voncken & Bögels, 2008).

However, it’s important to note that some individuals with SAD genuinely lack social skills, such as understanding social cues or knowing how to initiate and maintain conversations.

This deficiency can create a vicious cycle: their lack of social skills leads to negative social experiences, which in turn heightens their social anxiety.

This increased anxiety then further impedes the development of social skills, creating a self-perpetuating loop of social avoidance and anxiety (Spence et al., 1999).

Social skills deficits are usually addressed through social skills training (SST). You can click here to read our article on this approach in detail.

D. The Mind’s Labyrinth: Cognitive Biases and Biological Nuances

The Filters We Wear: Cognitive Biases in SAD

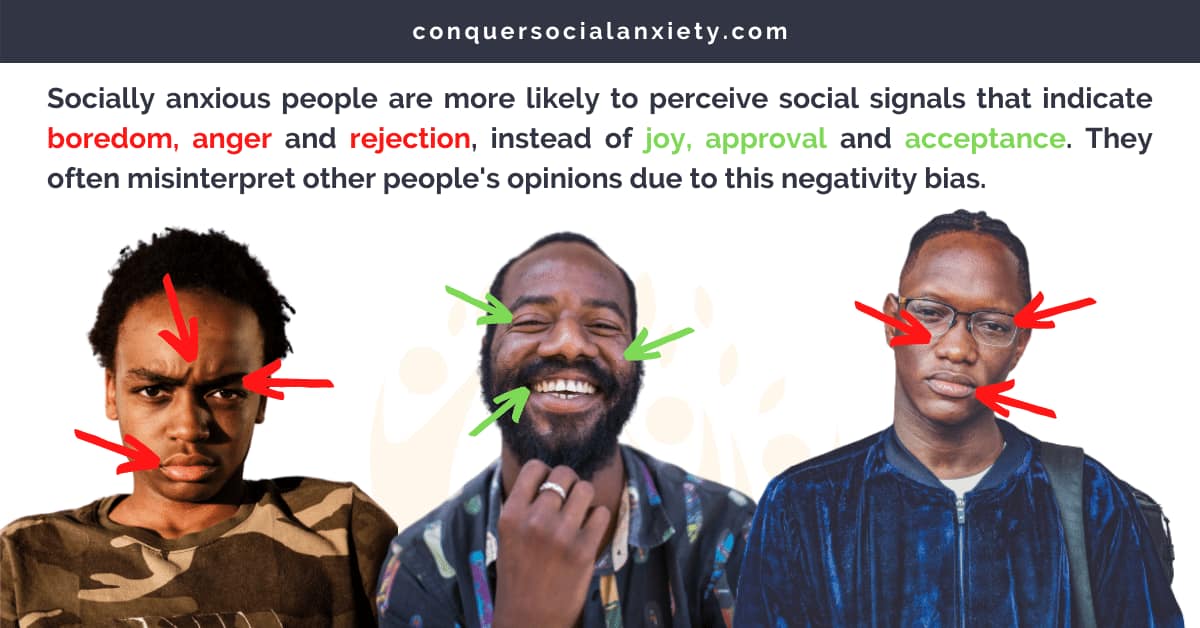

Our perception of the world is shaped by cognitive biases—systematic patterns of deviation from rationality in judgment.

These biases are influenced by our beliefs, moods, and thought patterns. For people with social anxiety, these cognitive biases can significantly affect how they perceive themselves and their surroundings in social situations (Alfano & Beidel, 2011).

While it’s still a subject of debate whether these biases are root causes or symptoms of SAD, they undoubtedly play a role in its manifestation.

Common Cognitive Biases in SAD:

- Catastrophizing: People with SAD often expect the worst possible outcome in social situations, such as believing a minor mistake will lead to public humiliation.

- Mind Reading: The belief that others are negatively judging or scrutinizing them, even when there’s no evidence to support this.

- Selective Attention: Focusing solely on negative aspects of a situation while ignoring any positive elements. For example, remembering only the one person who didn’t smile back in a room full of people.

- Overgeneralization: Taking a single negative event and seeing it as a never-ending pattern of defeat. For instance, if they stumble over words in one presentation, they may believe they are terrible at public speaking in general.

- Personalization: Believing they are the cause of external events. For example, if a friend is in a bad mood, they might think it’s because of something they did or said.

- Emotional Reasoning: Assuming that because they feel anxious, it means something bad is going to happen.

Understanding these cognitive biases can be the first step toward managing the symptoms of SAD.

By recognizing these thought patterns, individuals can work on challenging and changing them, often with the help of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

If you are interested in CBT for social anxiety, you can click here to read our introductory guide which covers the fundamentals.

The Body’s Response: Unveiling Biological Nuances

Beyond genetics, research has identified several intriguing biological markers that may contribute to SAD.

These findings add another layer of complexity to our understanding of the disorder, suggesting that it’s not solely a product of one’s environment or mental state.

Key Biological Markers:

- Heart Rate Reactivity: Studies have found that people with SAD often experience a greater increase in heart rate when tasked with public speaking (Heimberg et al., 1990; Hofmann et al., 1995; Levin et al., 1993). This heightened physiological response can exacerbate feelings of anxiety and make public speaking tasks particularly challenging.

- Amygdala Activation: The amygdala, often referred to as the ‘fear center’ of the brain, shows increased activation in people with SAD when exposed to certain stimuli (Birbaumer et al., 1998; Schwartz et al., 2003; Stein et al., 2002, Tillfors et al., 2001). This suggests that the brain’s emotional processing centers may be more sensitive in individuals with SAD, leading to heightened emotional responses in social situations.

What Does This Mean?

These biological markers indicate that the body’s natural response mechanisms may be altered in those with SAD.

While these findings don’t definitively prove causation, they do point to a biological basis for some of the symptoms experienced. Understanding these nuances can help in the development of targeted treatments, such as medications that can modulate heart rate or amygdala activity.

It’s important to note that these biological factors often interact with environmental and psychological factors, creating a complex interplay that makes each case of SAD unique.

As such, a multi-faceted approach to treatment, often involving both medication and psychotherapy, is usually the most effective.

By the way, you can click here to learn more about medication for social anxiety, and here to learn more about therapy for social anxiety.

E. The Cultural Fabric: How Society Shapes Social Anxiety

The Individualistic vs. Collectivist Paradigm

Cultural norms and values play a significant role in shaping the experience and prevalence of social anxiety disorder.

The impact of culture can be broadly categorized into two paradigms: individualistic and collectivist societies.

Individualistic Cultures:

In individualistic cultures, such as those prevalent in North America and Europe, there’s a strong emphasis on personal achievements, self-expression, and social confidence.

Outgoing and extroverted personalities are often celebrated, making it challenging for those with reserved or shy temperaments to fit in.

This societal preference can exacerbate feelings of inadequacy and contribute to the development or worsening of SAD (Alden & Taylor, 2004; Hart et al., 1999; Spokas & Cardaciotto, 2014).

Collectivist Cultures:

On the other hand, collectivist cultures, commonly found in Eastern Asia, value community harmony and interpersonal relationships.

In these societies, a reserved or shy temperament is often seen as a virtue rather than a drawback. As a result, the prevalence rates of SAD are generally lower in these cultures (Hofmann et al., 2011).

Understanding the cultural context is crucial for both diagnosing and treating SAD effectively. It also highlights the need for culturally sensitive approaches to mental health care, as what may be considered a disorder in one culture could be viewed differently in another.

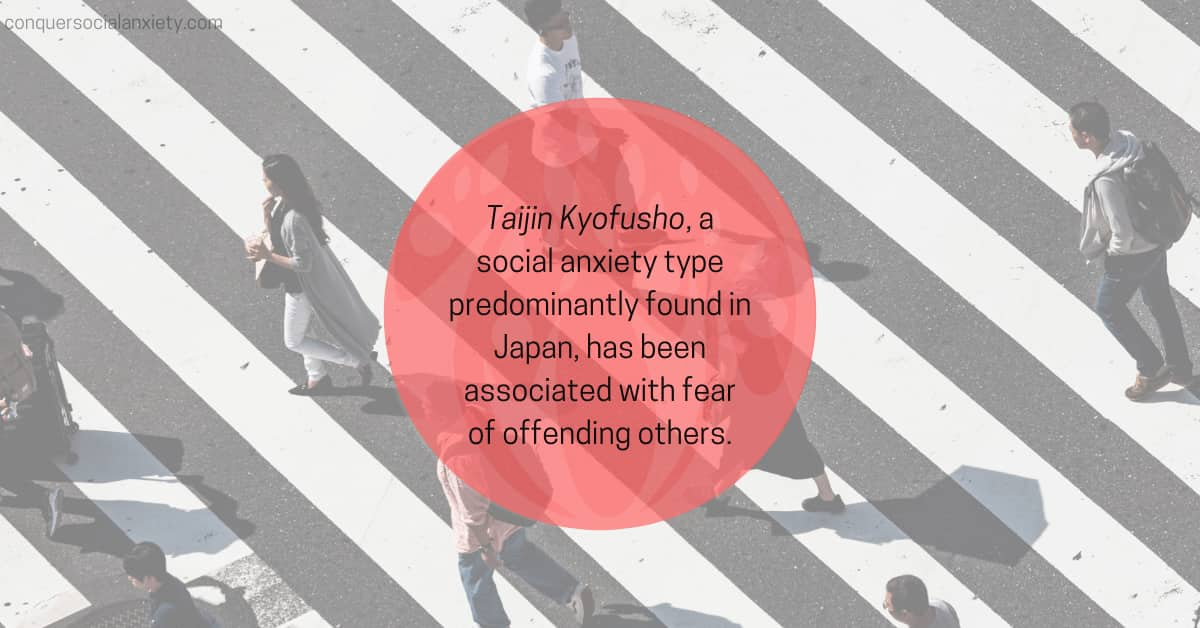

The Cultural Spectrum: From Taijin Kyofusho to Social Harmony

While social anxiety disorder is a globally recognized condition, its manifestation can vary significantly depending on cultural context.

One fascinating example is the phenomenon of Taijin Kyofusho, predominantly observed in Japan and other East Asian cultures.

Taijin Kyofusho:

Unlike the Western concept of SAD, which focuses on the fear of negative evaluation, Taijin Kyofusho is characterized by an intense fear of making others uncomfortable or offending them.

This form of social anxiety is deeply rooted in cultural norms that prioritize interdependence, social harmony, and collective well-being over individual desires or expressions (Rector et al., 2006).

The Cultural Influence:

The prevalence of Taijin Kyofusho highlights how cultural values and norms can shape the expression and experience of social anxiety.

In societies that value social harmony and interdependence, the fear shifts from how one is perceived by others to how one’s actions might negatively impact the community or social fabric.

A Broader Perspective:

Understanding these culturally specific forms of social anxiety enriches our global perspective on mental health.

It underscores the importance of considering cultural factors when diagnosing and treating social anxiety, ensuring that interventions are not only effective but also culturally sensitive.

Whether it’s the fear of negative evaluation in individualistic societies or the fear of causing discomfort in collectivist cultures, social anxiety exists on a broad cultural spectrum.

Recognizing this diversity is crucial for healthcare providers and researchers aiming to develop more inclusive and effective treatments.

Understanding social anxiety is a complex endeavor, requiring a multifaceted approach. As we’ve explored, its causes range from genetic and biological factors to environmental influences and cultural norms. But knowledge is the first step toward healing, and we’re here to help you on your journey.

- For a comprehensive look at treating SAD, check out our Complete Treatment Guide for Social Anxiety.

- If you’re looking for products and services designed to help you manage your social anxiety, don’t miss our Recommended Products and Services.

- For those who are new to the world of SAD or are looking to understand the basics, our Guide Covering the Basics of Social Anxiety is a must-read.

Take the First Step: Our Free 7-Day Email Course

If you’re ready to take the first step toward managing your social anxiety, sign up for our Free 7-Day Email Course. This course will equip you with everything you need to know about your condition and how to improve it.

Alden, L. E., & Taylor, C. T. (2004). Interpersonal processes in social phobia. Clinical psychology review, 24(7), 857–882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.006

Alfano, C. A., & Beidel, D. C. (Eds.). (2011). Social anxiety in adolescents and young adults: Translating developmental science into practice. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12315-000

Aouizerate, B., Martin-Guehl, C., & Tignol, J. (2004). Neurobiologie et pharmacothérapie de la phobie sociale [Neurobiology and pharmacotherapy of social phobia]. L’Encephale, 30(4), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-7006(04)95442-5

Birbaumer, N., Grodd, W., Diedrich, O., Klose, U., Erb, M., Lotze, M., Schneider, F., Weiss, U., & Flor, H. (1998). fMRI reveals amygdala activation to human faces in social phobics. Neuroreport, 9(6), 1223–1226. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-199804200-00048

Bögels, S. M., van Oosten, A., Muris, P., & Smulders, D. (2001). Familial correlates of social anxiety in children and adolescents. Behaviour research and therapy, 39(3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00005-x

Bohlin, G., Hagekull, B., & Rydell, A.-M. (2000). Attachment and social functioning: A longitudinal study from infancy to middle childhood. Social Development, 9(1), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00109

Bruch, M. A., Heimberg, R. G., Berger, P., & Collins, T. M. (1989). Social phobia and perceptions of early parental and personal characteristics. Anxiety Research, 2(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/08917778908249326

Cartwright-Hatton, S., Hodges, L., & Porter, J. (2003). Social anxiety in childhood: the relationship with self and observer rated social skills. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 44(5), 737–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00159

Cartwright-Hatton, S., Tschernitz, N., & Gomersall, H. (2005). Social anxiety in children: Social skills deficit, or cognitive distortion? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.003

Clark, J. V., & Arkowitz, H. (1975). Social anxiety and self-evaluation of interpersonal performance. Psychological Reports, 36(1), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1975.36.1.211

Condren, R. M., O’Neill, A., Ryan, M. C., Barrett, P., & Thakore, J. H. (2002). HPA axis response to a psychological stressor in generalised social phobia. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 27(6), 693–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00070-1

Cook, M., & Mineka, S. (1991). Selective associations in the origins of phobic fears and their implications for behavior therapy. In P. R. Martin (Ed.), Handbook of behavior therapy and psychological science: An integrative approach (pp. 413–434). Pergamon Press.

Hart, T. A., Turk, C. L., Heimberg, R. G., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1999). Relation of marital status to social phobia severity. Depression and anxiety, 10(1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1999)10:1<28::aid-da5>3.0.co;2-i

Heimberg, R. G., Hope, D. A., Dodge, C. S., & Becker, R. E. (1990). DSM-III-R subtypes of social phobia. Comparison of generalized social phobics and public speaking phobics. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 178(3), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199003000-00004

Hofmann, S. G., Anu Asnaani, M. A., & Hinton, D. E. (2010). Cultural aspects in social anxiety and social anxiety disorder. Depression and anxiety, 27(12), 1117–1127. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20759

Hofmann, S. G., Newman, M. G., Ehlers, A., & Roth, W. T. (1995). Psychophysiological differences between subgroups of social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(1), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.224

Levin, A. P., Saoud, J. B., Strauman, T., Gorman, J. M., Fyer, A. J., Crawford, R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1993). Responses of “generalized” and “discrete” social phobics during public speaking. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 7(3), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/0887-6185(93)90003-4

Muris, P., Mayer, B., & Meesters, C. (2000). Self-reported attachment style, anxiety, and depression in children. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 28(2), 157–162. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2000.28.2.157

Norton, P. J., & Hope, D. A. (2001). Analogue observational methods in the assessment of social functioning in adults. Psychological Assessment, 13(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.13.1.59

Öst L. G. (1985). Ways of acquiring phobias and outcome of behavioral treatments. Behaviour research and therapy, 23(6), 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(85)90066-x

Öst, L.-G., & Hugdahl, K. (1981). Acquisition of phobias and anxiety response patterns in clinical patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 19(5), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(81)90134-0

Rapee, R. M., & Abbott, M. J. (2006). Mental representation of observable attributes in people with social phobia. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 37(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.01.001

Rapee, R. M., & Lim, L. (1992). Discrepancy between self- and observer ratings of performance in social phobics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(4), 728–731. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.101.4.728

Rector, N.A., Kocovski, N.L. & Ryder, A.G. Social Anxiety and the Fear of Causing Discomfort to Others. Cogn Ther Res 30, 279–296 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9050-9

Schneier, F. R., Liebowitz, M. R., Abi-Dargham, A., Zea-Ponce, Y., Lin, S. H., & Laruelle, M. (2000). Low dopamine D(2) receptor binding potential in social phobia. The American journal of psychiatry, 157(3), 457–459. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.457

Schwartz, C. E., Wright, C. I., Shin, L. M., Kagan, J., & Rauch, S. L. (2003). Inhibited and uninhibited infants “grown up”: Adult amygdalar response to novelty. Science, 300(5627), 1952–1953. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1083703

Spence, S. H., Donovan, C., & Brechman-Toussaint, M. (1999). Social skills, social outcomes, and cognitive features of childhood social phobia. Journal of abnormal psychology, 108(2), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.211

Spence, S. H., & Rapee, R. M. (2016). The etiology of social anxiety disorder: An evidence-based model. Behaviour research and therapy, 86, 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.007

Spokas, M. E., & Cardaciotto, L. (2014). Heterogeneity within social anxiety disorder. In J. W. Weeks (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of social anxiety disorder (pp. 247–267). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118653920.ch12

Stein, M. B., Goldin, P. R., Sareen, J., Zorrilla, L. T., & Brown, G. G. (2002). Increased amygdala activation to angry and contemptuous faces in generalized social phobia. Archives of general psychiatry, 59(11), 1027–1034. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1027

Stopa, L., & Clark, D. M. (1993). Cognitive processes in social phobia. Behaviour research and therapy, 31(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(93)90024-o

Stravynski, A., Elie, R., & Franche, R. L. (1989). Perception of early parenting by patients diagnosed avoidant personality disorder: a test of the overprotection hypothesis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 80(5), 415–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb02999.x

Tillfors, M., Furmark, T., Marteinsdottir, I., Fischer, H., Pissiota, A., Långström, B., & Fredrikson, M. (2001). Cerebral blood flow in subjects with social phobia during stressful speaking tasks: a PET study. The American journal of psychiatry, 158(8), 1220–1226. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1220

Voncken, M. J., & Bögels, S. M. (2008). Social performance deficits in social anxiety disorder: reality during conversation and biased perception during speech. Journal of anxiety disorders, 22(8), 1384–1392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.02.001

Wood, J. J., McLeod, B. D., Sigman, M., Hwang, W. C., & Chu, B. C. (2003). Parenting and childhood anxiety: theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 44(1), 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00106

About the Author: Martin Stork

Martin is a professional psychologist with a background in physical therapy. He has organized and led various support groups for people with social anxiety in Washington, DC and Buenos Aires, Argentina. He is the founder of Conquer Social Anxiety Ltd, where he operates as a writer, therapist and director. You can click here to find out more about Martin.